Friday, 17 December 2010

Monday, 8 November 2010

Tuesday, 2 November 2010

Sunday, 31 October 2010

Saturday, 30 October 2010

Thursday, 14 October 2010

My prayer for the time being

1 [For the choirmaster For flutes Psalm Of David] Give ear to my words, Yahweh, spare a thought for my sighing.

2 Listen to my cry for help, my King and my God! To you I pray,

3 Yahweh. At daybreak you hear my voice; at daybreak I lay my case before you and fix my eyes on you.

4 You are not a God who takes pleasure in evil, no sinner can be your guest.

5 Boasters cannot stand their ground under your gaze. You hate evil-doers,

6 liars you destroy; the violent and deceitful Yahweh detests.

7 But, so great is your faithful love, I may come into your house, and before your holy temple bow down in reverence of you.

8 In your saving justice, Yahweh, lead me, because of those who lie in wait for me; make your way plain before me.

9 Not a word from their lips can be trusted, through and through they are destruction, their throats are wide -- open graves, their tongues seductive.

10 Lay the guilt on them, God, make their intrigues their own downfall; for their countless offences, thrust them from you, since they have rebelled against you.

11 But joy for all who take refuge in you, endless songs of gladness! You shelter them, they rejoice in you, those who love your name.

12 It is you who bless the upright, Yahweh, you surround them with favour as with a shield.

2 Listen to my cry for help, my King and my God! To you I pray,

3 Yahweh. At daybreak you hear my voice; at daybreak I lay my case before you and fix my eyes on you.

4 You are not a God who takes pleasure in evil, no sinner can be your guest.

5 Boasters cannot stand their ground under your gaze. You hate evil-doers,

6 liars you destroy; the violent and deceitful Yahweh detests.

7 But, so great is your faithful love, I may come into your house, and before your holy temple bow down in reverence of you.

8 In your saving justice, Yahweh, lead me, because of those who lie in wait for me; make your way plain before me.

9 Not a word from their lips can be trusted, through and through they are destruction, their throats are wide -- open graves, their tongues seductive.

10 Lay the guilt on them, God, make their intrigues their own downfall; for their countless offences, thrust them from you, since they have rebelled against you.

11 But joy for all who take refuge in you, endless songs of gladness! You shelter them, they rejoice in you, those who love your name.

12 It is you who bless the upright, Yahweh, you surround them with favour as with a shield.

Monday, 11 October 2010

The foundation of the modern State

Translating today a short treatise on criminal law. Found something interesting:

The iustitia communtativa in the Politics and Ethics of Aristotle used to be the foundation of retributive criminal law. At the same time it is the very foundation of the legitimation of the state itself, because a pre-modern state represents the moral status of the society. The modern state in comparison doesn't claim to represent the moral status of the society (it is any way impossible in a multi-cultural society like that in the industrialized world), instead, its only legitimation lies in the alleged guarantee of individual freedom. So we get the problem that retributive penalty can't be justified through its function of restitution of the normative legal status which is injured by criminal deeds. But how can a state whose legitimation lies in the individual freedom claim to restrict the freedom of its citizens in form of penalty? That is the dilemma for retributive theory of legal penalty for criminal deeds.

The iustitia communtativa in the Politics and Ethics of Aristotle used to be the foundation of retributive criminal law. At the same time it is the very foundation of the legitimation of the state itself, because a pre-modern state represents the moral status of the society. The modern state in comparison doesn't claim to represent the moral status of the society (it is any way impossible in a multi-cultural society like that in the industrialized world), instead, its only legitimation lies in the alleged guarantee of individual freedom. So we get the problem that retributive penalty can't be justified through its function of restitution of the normative legal status which is injured by criminal deeds. But how can a state whose legitimation lies in the individual freedom claim to restrict the freedom of its citizens in form of penalty? That is the dilemma for retributive theory of legal penalty for criminal deeds.

Labels:

Philosophy

Wednesday, 15 September 2010

Monday, 16 August 2010

Reading the "History of the Romish Literature" of Manfred Fuhrmann (Part I)

1) the Latin language: only the idiom of the region Latium, but together with the Idea of the State the Romish idiom became the normative language for the west part of the Roman Empire, especially for Iberia, North Africa, the region around the Black See. The Rumanian language of today is developed from Latin. The development of the Latin language to its classic form as a normative language of the Empire includes the "Rhotacism" ('s' between vocals is substituted by 'r'); the disappearance of Diphthongs; the three verbal forms of the Indo-German language family, which survive in Greek, were reduced: the aorists were reduced to the present and perfect forms; the grammar became more strict.

2) the begin of the Romish literature: 240 before Christus with the translation of Greek comedies and tragedies. Greeks began to settle down in Italy and had a large influence on the Etruscan culture. The Romans didn't have their own myths and thus the Greek literature must have had also an influence on the development of the Roman religion. Also the Lex XII tabularum was the result of the influence of Greek culture. The Romish religion is more abstract, the gods were identified with their power and acts, while the Greek religion is more anthropomorphic. The symbols of the power: faces, lictores and the sella curulis go back to the Etruscan influence. Livius wrote about the Etruscan people: "Gens ante omnes alias eo magis dedita religionibus, quod excelleret arte colendi eas". The fights of the gladiators also go back to Etruscan customs. Before the direct influence of the Greeks the Romans didn't know the difference between proses and poetry. They used rhythmic lines in the proses, and called text written in such a way "Carmen". One kind of verses was known: versus Saturnius (allusion of the Golden age), which was used by Livius Andronicus and Naevius. But Ennius substituted it through the Greek hexameter. Two examples of the Versus Saturnius: "Adesto, Tiberine, cum tuis undis" (a prayer) and "Virum mihi, Camena insece versutum" (the translation of "Odysseus" by Livius Andronicus). Other kinds of literature: nenia, accompanied by flute, lamentation of the dead; heroic songs, sung at the meal, and harvest songs. Besides these one can also find the Fabula Atellana, the Laudatio Funebris (a specific Roman genre), and the Annales.

3) the development of the Romish Literature after the muster of the Greek literature: ludi Romani - ludi scaenici (theatre plays). The school system of the Greeks: all children could learn gymnastics, music, writing, reading and calculating. Children from better families could go later to school to learn literature, grammar and stile. Later, a small number of privileged young men could learn rhetoric. The Romans copied this kind of school system. The Roman schools were private, while the theatre plays were organised by the State. Not only in these two domains did the Greek culture influence the Roman culture, but also regarding the Roman customs.

(To be continued)

Labels:

Latin,

Literature

Friday, 13 August 2010

The Death as Cynic - Johannes von Tepl's "The Ploughman and the Death"

It is a short dialogue between a Ploughman, who ploughed with feather (that means he was not a peasant, but a clerk) written in Middle High German. The ploughman laments the early death of his wife Margaretha, whom he loves dearly, and accused the Death of injustice. The Death answers in plural form "We", like God do in the second last chapter of this dialogue. The Death attests that the wife of the ploughman has been a very virtuous woman, but refuses to acknowledge the injustice down to the ploughman. As everyone who is once born must die, disregarding with what age and who. The ploughman lists the virtues and great deeds of man, but the Death laughs at the folly of man. The ploughman praises the luck of family life, the Death numbers all the disadvantages of a married life. The ploughman sings a hymn of beautiful and virtuous women, the Death sneers and plays the role of the worst misogynist. The ploughman asks sincerely for advices to make amend of sorry, the Death stresses the uselessness of all hope to find remedy for the loss. In the end God comes to settle the quarrel, and tells the Death to be humble as the power of Death comes only from God. The ploughman is praised for his courage but is also asked to rest the case, because, as God is written as saying: "Every human being is obliged to give the Death his life, the Earth his body, and Us his soul" (chapter 33). Thus, the ploughman calms down and prays for the soul of his wife. The last chapter (34) consists in a very long and moving prayers which assembles a litany, in which the ploughman addresses God in all his attributes as the Creator and Lord of our life and existence.

But I don't quite see which function the quarrel can have: the Death appears in the role of a cynic. Life is nothing than sorrow and hardship, human beings are bad, hope and joy make only the loss of what is dear to us more painful. The human body is nothing than a cadaver, given over to the worms. The ploughman is in comparison a lover of the mankind and tries his best to defend the value of life and dignity of man, because, as he stresses on many places, man is the creature of God so can't be as bad and unworthy as the Death sees him. But neither party lets himself be convinced by only one point of his opponent. So it is a riddle to me what the point of this dialogue is. Perhaps the writer only wants to show the unreconcilable antithesis of the human existence: Life and Death, Joy and Sorrow. Without the Christian Faith it will ends in an aporia. Without the Christian Faith we will go back to the hopeless melancholy of Horace, whose only advices to overcome this antithesis is to carpe diem, and drown your sorrow in the drunkenness. While the Death in this dialogue tells one, despite all his sneers, to "avoid the evil and do what is good, to search for the peace and to keep it constantly. And one should not overestimate the earthly joy and possessions. Above all, one should have a pure conscious". So the Death as cynic is not a hedonist nor a nihilist. He is a curing cynic like the cynics in Lucian's Satire: the cynic is there to keep people honest and to free their soul from foul spots and superfluous sorrow and conceitedness.

One chapter (chapter 16) where the Death describes himself is especially interesting, which I translate as in the following:

"You ask, what we are: We are nothing and are nevertheless something. We are nothing, because we have no life nor substance, no figure nor duration (unterstand: not quite sure what meaning this word in Mhd. has). We are again something, because we are the End of Life, the End of the Existence, the Begin of Nothing, a thing between both of them. [...]".

Labels:

Literature

Thursday, 12 August 2010

De vera Religione - Part I: Plato and Christianity

Yesterday in a hurry I bought the "De vera religione" for the train trip, didn't read it much though. Today I read Chapter I to VII. To be noted is the description of Plato as a crypt Christian. The search of Plato after the stable, never changing beauty is taken by Augustine as the search after God. The similitude between Plato's thinking and the Christian teaching consists according to Augustine in the followings: 1) the truth should be seen through the mind, not through eyes (non corporeis oculis sed pura mente veritatem videri), and that to adhere to this truth is the perfect luck, and that to achieve this one must live an ascetic life without the distortion and delusion which are brought up by the lusts; 2) to see the unchanging beauty, the soul must be healthy (sana); 3) among all creatures only the rational and intellectual soul is able to see the eternity of God and to enjoy the eternal life. But Augustine opines that Plato was afraid to act against the conventions of his society and thus didn't give up a life in the world and to seek God in a life style whilst all the secular interests were left behind. In comparison, the Christians achieved what Plato originally intended to.

From Chapter V to VII Augustine writes that the True Religion is only in the Catholic Church. His definition of what is catholic is quite interesting: that is the community which is free from heresy and schism (which comes up due to the arrogance). Although people can have the same liturgy, but the difference in belief can excommunicate one from the catholic community. And it is possible, thus Augustine, that very orthodox and pious people can be excommunicated through mistake. But a true saint will endure all this injustice and will never start an act of disobedience (nr. 33: "quam contumeliam vel iniuriam suam cum patientissime pro ecclessiae pace tulerint neque ullas novitates vel schismatis vel heresis moliti fuerint, docebunt homines quam vero affectu et quanta sinceritate caritatis deo serviendum sit").

To be continued.

Labels:

Theology

Sunday, 8 August 2010

Death in Life (Horace's Carmen 1, 4)

The motif of the famous "Carpe Diem" (1, 11) poem of Horace can also be found in his Carmen 1, 4, where he wrote in the first three verses about the Joy of Spring. But in the first line of the fourth verse the word "Death" appeared: pallida Mors aequo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas regumque turris. And he mentioned also that we should not make plan and have expectations for times long after: o beate Sesti, vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam; iam te premet nox fabulaeque Manes.

to: Manes see the tombstone below

written in Archilochium tertium.

But why! Is it common for the ancient literature? This melancholy. I don't think so. Horace seems to be too sentimental for an ancient poet. No unreflected serenity which is supposed to be so characteristic for the ancient world. Always with the antithesis of Life and Death, oh the Death triumphs in the end! But for my taste, this reflection is again too shallow. It is without the metaphysical depth of the baroque poetry, without the heroic attitude of a baroque man.

And does it move me, this poem? Not so much like that of his Carmen 1, 11. Why? Because it is only about the shortness of one's own life - though he talks to Sestius, but he just means the pleasure of one's life is so transient. In comparison, Carmen 1, 11 talks about the shortness of the time two friends (lovers) can be together. And only the latter pains me. Not only Death can part two, oh lucky is she who parts from her friend only through Death. To part while still in life is a greater pain! And do I fear Death? I don't. But people say I only say I fear Death not because I am still young. Perhaps they are right.

to: Manes see the tombstone below

written in Archilochium tertium.

But why! Is it common for the ancient literature? This melancholy. I don't think so. Horace seems to be too sentimental for an ancient poet. No unreflected serenity which is supposed to be so characteristic for the ancient world. Always with the antithesis of Life and Death, oh the Death triumphs in the end! But for my taste, this reflection is again too shallow. It is without the metaphysical depth of the baroque poetry, without the heroic attitude of a baroque man.

And does it move me, this poem? Not so much like that of his Carmen 1, 11. Why? Because it is only about the shortness of one's own life - though he talks to Sestius, but he just means the pleasure of one's life is so transient. In comparison, Carmen 1, 11 talks about the shortness of the time two friends (lovers) can be together. And only the latter pains me. Not only Death can part two, oh lucky is she who parts from her friend only through Death. To part while still in life is a greater pain! And do I fear Death? I don't. But people say I only say I fear Death not because I am still young. Perhaps they are right.

Labels:

Latin

Wednesday, 4 August 2010

Die Oratio Dominica (Chapter 5 of "Jesus of Nazareth"

Recapitulation of chapter 4: the Sermon on the Mountain tells us how to be a human being. And a real anthropology is only possible in the light of a theology.

1) Then Pope Benedict turns to the version of Oratio Dominica in the Matthew's Gospel: the evangelist tells us how to pray in a right way. Not the human being should be in the centre of the prayer, but only the love to God. As the Revelation says, God calls everyone with his own name, which nobody knows other than God (Rev. 2, 17). The Oratio Dominica is a We-Prayer, that means, only in the Church we can reach God as individuals! So in a correct prayer one should brings one's innermost personality to God but at the same time in a community. The other false way to pray is the thoughtless repetition, as we are told by the evangelist.

In the prayer we intensify our relationship to God. But not only the awareness of being together with God is needed, but also concretes formulas of prayers. The prayers of Israel and later the prayers of the Church are the school of praying and also lead to a deep transformation of our life.

Saint Benedict wrote in his Regula: Mens nostra concordet voci nostrae (cf. also Reg 19, 7). But in the prayers of psalms and the prayers in the liturgy of the Church it is different: our mind must be obedient to the Word, in this Word God comes to help us to pray and find Him.

2) the version of Luke's Gospel: the Father-Son-relationship in the Oratio Dominica. The inner unity with God.

3) Structure of the Oratio Dominica:

Our Father:

three petitions with "thou", and 7 with "we", thus its structure is parallel to Decalogue. As we only know the Father through the Son, so the prayer begins with the addressing of God as "Father". And God is our Father, because our life comes from Him as the Creator and belongs to Him. To be children of God is to be the followers of Christ. But only Jesus Christ can say: "my Father", but we all must say "our Father".

Who art in heaven:

Name of God: I am who I am (Ex 3,6).

Thy Kingdom come:

The Kingdom of God comes over a pure heart, and this is what we pray for.

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven:

Jesus Christ is the heaven, and God's will is done in Heaven. We on the earth should follow Christ in obedience, so that we can come nearer to heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread:

As Cyprian already said, we pray for OUR daily bread, no one should pray for his own alone. And he said also, that who he must pray for the bread of today, is poor, so the followers of Christ are poor because they give up their property for God's sake. And the others, who haven't went so far, should stay in solidarity with these who try to love God in such a radical way (the religious). And of course already explained by the Fathers of the Church as the prayer for Eucharist.

and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us:

This is a christological prayer, not merely a moral appeal, because the forgiveness of our Sins costed our Lord the Blood of His Son.

And lead us not into temptation:

Parallel to Hiob: not that God will tempt us into sin, but that he will send us trial, which we withstand ad gloriam Dei. But we pray at the same time, that God never let us alone in our trial.

but deliver us from evil:

with this prayer we pray for the Kingdom of God. And that is why in the Liturgy after the Pater noster the Priest prays further: Libera nos, quaesumus, Domine, ab omnibus malis, praeteritis, praesentibus, et futuris, et intercedente beata et gloriosa semper Virgine Dei Genitrice Maria, cum beatis Apostolis tuis Petro et Paulo, atque Andrea, et omnibus Sanctis, da propitius pacem in diebus nostris, ut ope misericordiae tuae adjuti, et a peccato simus semper liberi, et ab omni perturbatione securi. Per eumdem Dominum nostrum Jesum Christum Filium tuum. Qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitate Spiritus Sancti Deus. Per omnia saecula saeculorum. This Embolism, thus Pope Benedict, shows the human side of the Church, which is very much in need of deliverance.

1) Then Pope Benedict turns to the version of Oratio Dominica in the Matthew's Gospel: the evangelist tells us how to pray in a right way. Not the human being should be in the centre of the prayer, but only the love to God. As the Revelation says, God calls everyone with his own name, which nobody knows other than God (Rev. 2, 17). The Oratio Dominica is a We-Prayer, that means, only in the Church we can reach God as individuals! So in a correct prayer one should brings one's innermost personality to God but at the same time in a community. The other false way to pray is the thoughtless repetition, as we are told by the evangelist.

In the prayer we intensify our relationship to God. But not only the awareness of being together with God is needed, but also concretes formulas of prayers. The prayers of Israel and later the prayers of the Church are the school of praying and also lead to a deep transformation of our life.

Saint Benedict wrote in his Regula: Mens nostra concordet voci nostrae (cf. also Reg 19, 7). But in the prayers of psalms and the prayers in the liturgy of the Church it is different: our mind must be obedient to the Word, in this Word God comes to help us to pray and find Him.

2) the version of Luke's Gospel: the Father-Son-relationship in the Oratio Dominica. The inner unity with God.

3) Structure of the Oratio Dominica:

Our Father:

three petitions with "thou", and 7 with "we", thus its structure is parallel to Decalogue. As we only know the Father through the Son, so the prayer begins with the addressing of God as "Father". And God is our Father, because our life comes from Him as the Creator and belongs to Him. To be children of God is to be the followers of Christ. But only Jesus Christ can say: "my Father", but we all must say "our Father".

Who art in heaven:

Name of God: I am who I am (Ex 3,6).

Thy Kingdom come:

The Kingdom of God comes over a pure heart, and this is what we pray for.

Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven:

Jesus Christ is the heaven, and God's will is done in Heaven. We on the earth should follow Christ in obedience, so that we can come nearer to heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread:

As Cyprian already said, we pray for OUR daily bread, no one should pray for his own alone. And he said also, that who he must pray for the bread of today, is poor, so the followers of Christ are poor because they give up their property for God's sake. And the others, who haven't went so far, should stay in solidarity with these who try to love God in such a radical way (the religious). And of course already explained by the Fathers of the Church as the prayer for Eucharist.

and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us:

This is a christological prayer, not merely a moral appeal, because the forgiveness of our Sins costed our Lord the Blood of His Son.

And lead us not into temptation:

Parallel to Hiob: not that God will tempt us into sin, but that he will send us trial, which we withstand ad gloriam Dei. But we pray at the same time, that God never let us alone in our trial.

but deliver us from evil:

with this prayer we pray for the Kingdom of God. And that is why in the Liturgy after the Pater noster the Priest prays further: Libera nos, quaesumus, Domine, ab omnibus malis, praeteritis, praesentibus, et futuris, et intercedente beata et gloriosa semper Virgine Dei Genitrice Maria, cum beatis Apostolis tuis Petro et Paulo, atque Andrea, et omnibus Sanctis, da propitius pacem in diebus nostris, ut ope misericordiae tuae adjuti, et a peccato simus semper liberi, et ab omni perturbatione securi. Per eumdem Dominum nostrum Jesum Christum Filium tuum. Qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitate Spiritus Sancti Deus. Per omnia saecula saeculorum. This Embolism, thus Pope Benedict, shows the human side of the Church, which is very much in need of deliverance.

Labels:

Pope Benedict,

Theology

Saturday, 31 July 2010

The Sermon on the Mountain (reading the Jesus Book of Pope Benedict - First Volume)

(Chapter 4) The Sermon on the Mountain is a passage which is often misused by the modernists to show that nothing is needed to achieve the salvation, no study, no observation of the laws, only a simple mind suffices. And liberal theologians tend to see this sermon as an abolishment of the Old Law, including the Decalogue.

Pope Benedict shows us that not an iota of the Old Law can be abolished, and tells us what the real meaning of this passage is. What is striking for me is how Pope Benedict shows the continuity between the Sermon on the Mountain and the Old Testament, especially the Psalms. It is also very interesting that he mentions on many places his good friend Rabbi Neusner. Thus, the liberal thesis that the Sermon on the Mountain presents a new Ethics and abolish the old Ethics of OT is refuted. And with "the poor" mentioned in the sermon are not meant impoverished people, as poverty doesn't lead to salvation, but those who are poor before God, that is, those, who don't boast of what they have done. The Holy Father cites a sentence of Therese of Lisieux: "I will stand before God with empty hands and keep them open". It means, we open our hands to receive the Grace of the Lord. The poor are also those who decide to abandon earthly comfort to follow the example of Christ, like Francis of Assisi did.

The Sermon on the Mountain, thus Pope Benedict, is a hidden Christology: as God took the flesh of man and died for our sake. So the Sermon on the Mountain tells us how to be the true imitator of Christ: to love, and that means to abandon every kind of egoism. And Pope Benedict wrote: "in opposite to the alluring glamour of Nietzsche's picture of man this way (of imitation Christi) appears poor, but it is the real way of life to ascend, only on the way of love the richness of life and the magnitude of human vocation become available".

In the second part of this chapter Pope Benedict tells us that according to the Jewish Tradition, the Messiah is supposed to bring his own "Torah". So the question is raised again: do the new laws substitute the old ones? The answer of Pope Benedict is: they don't abolish the old laws, but fulfil them. A very interesting passage which our Pope quotes from the book of Rabbi Neusner is: Jesus has, in comparison to the prophets, not a single new law! Jesus said only, come and follow me (Mt. 19, 20). And that is the reason why Rabbi Neusner decides that he remains in the Jewish Religion, because Rabbi Neusner finds that to follow Jesus will be contrary to the first (to honour God alone and to keep Sabbath) and the fourth (to honour father and mother) commandment. Pope Benedict shows that these commandments are fulfilled in the social teachings of the Church. And Pope Benedict shows also that in the Torah Israel is not only for its own people there, but is to become the light of all people in the world. The aim of the Holy Father is, as I see it, to show that Jesus Christ stands in the continuity with the OT, though he brought very new and revolutionary teachings. But his teachings can also be found in the inner structure of the Torah.

This approach of our Holy Father to the NT is very interesting. It is not only in the hermeneutic tradition of the analogical reading, but also in a new sense as he is using the Jewish Tradition of Bible reading to support our Christian teachings. It will not only teach us to have more respect and insight for the Jewish Tradition which is in part also ours, but can also be useful to explain to the Jews what Christianity is, and even persuade some of them more easily, as the Scripture is central for the Jewish Religion.

Pope Benedict shows us that not an iota of the Old Law can be abolished, and tells us what the real meaning of this passage is. What is striking for me is how Pope Benedict shows the continuity between the Sermon on the Mountain and the Old Testament, especially the Psalms. It is also very interesting that he mentions on many places his good friend Rabbi Neusner. Thus, the liberal thesis that the Sermon on the Mountain presents a new Ethics and abolish the old Ethics of OT is refuted. And with "the poor" mentioned in the sermon are not meant impoverished people, as poverty doesn't lead to salvation, but those who are poor before God, that is, those, who don't boast of what they have done. The Holy Father cites a sentence of Therese of Lisieux: "I will stand before God with empty hands and keep them open". It means, we open our hands to receive the Grace of the Lord. The poor are also those who decide to abandon earthly comfort to follow the example of Christ, like Francis of Assisi did.

The Sermon on the Mountain, thus Pope Benedict, is a hidden Christology: as God took the flesh of man and died for our sake. So the Sermon on the Mountain tells us how to be the true imitator of Christ: to love, and that means to abandon every kind of egoism. And Pope Benedict wrote: "in opposite to the alluring glamour of Nietzsche's picture of man this way (of imitation Christi) appears poor, but it is the real way of life to ascend, only on the way of love the richness of life and the magnitude of human vocation become available".

In the second part of this chapter Pope Benedict tells us that according to the Jewish Tradition, the Messiah is supposed to bring his own "Torah". So the question is raised again: do the new laws substitute the old ones? The answer of Pope Benedict is: they don't abolish the old laws, but fulfil them. A very interesting passage which our Pope quotes from the book of Rabbi Neusner is: Jesus has, in comparison to the prophets, not a single new law! Jesus said only, come and follow me (Mt. 19, 20). And that is the reason why Rabbi Neusner decides that he remains in the Jewish Religion, because Rabbi Neusner finds that to follow Jesus will be contrary to the first (to honour God alone and to keep Sabbath) and the fourth (to honour father and mother) commandment. Pope Benedict shows that these commandments are fulfilled in the social teachings of the Church. And Pope Benedict shows also that in the Torah Israel is not only for its own people there, but is to become the light of all people in the world. The aim of the Holy Father is, as I see it, to show that Jesus Christ stands in the continuity with the OT, though he brought very new and revolutionary teachings. But his teachings can also be found in the inner structure of the Torah.

This approach of our Holy Father to the NT is very interesting. It is not only in the hermeneutic tradition of the analogical reading, but also in a new sense as he is using the Jewish Tradition of Bible reading to support our Christian teachings. It will not only teach us to have more respect and insight for the Jewish Tradition which is in part also ours, but can also be useful to explain to the Jews what Christianity is, and even persuade some of them more easily, as the Scripture is central for the Jewish Religion.

Labels:

Pope Benedict,

Theology

Monday, 19 July 2010

The Reception of Homer in the Caroligian Renaissance?

I know that Homer was not read during the most time of the medium aevum. Greek was seldom studied. And as far as I know, there were no translations of Homer's Iliad and Odysseus. But it astonishes me to read that during the Carolingian Renaissance students were to read Homer. Well, at that time, Greek was still studied. Even Hincmar of Reims translated the Pseudo-Dionysius as well as John Scottus Eriugena. But still one expects little that they did read Homer. Did they learn from Homer's works through a second hand source, or was Homer read in original? This question I still have to pursuit. But it astonishes one not little when one reads from the classic allusions in a Latin poem by Eriugena (very long, typed according to the MGH edition, there nr. 2). But it doesn't show that he did read Homer himself. This poems goes on very quickly to the praise of the Cross and Christus. Eriugena wants to show that the Christian Reign is more glorious than the ancient reigns:

Hellinus Troasque suos cantarat Homerus,

Romuleum prolem finxerat ipse Maro;

At nos caeligenum regis pia facta canamus.

Continuo cursu quem canit orbis ovans.

Illis Iliacas flammas subitasque ruinas

Eroumque Machas dicere ludus erat;

Ast nobis Christum devicto principe mundi

Sanguine perfusum psallere dulce sonat.

Illi composito falso sub imagine veri

Fallere condocti versibus Arcadicis;

Nobis virtutem patris veramque sophiam

Ymnizare licet laudibus eximiis.

Moysarum cantus, ludos satyrasque loquaces

Ipsis usus erat plaudere per populos:

Dicta prophetarum nobis modulamine pulchro

Consona procedunt cordibus ore fide.

Nunc igitur Christi videamus summa tropea

Ac nostrae mentis sidera perspicua.

Ecce crucis lignum quadratum continet orbem.

In quo pendebat sponte sua dominus

Et verbum patris dignatum sumere carnem

In quo pro nobis hostia grata fuit.

Aspice confossas palmas humerosque pedesque,

Spinarum serto tempora cincta fero.

In medio lateris reserato fonte salutis

Ves haustus, sanguis et unda, fluut.

Unda lavat totum veteri peccamine mundum,

Sanguis mortales nos facit esse deos.

Binos adde reos pendentes arbore bina:

Par fuerat meritum, gratia dispar erit.

Unus cum Christo paradisi limina vidit.

Alter sulphureae mersus in ima stygis.

Eclypsis solis, lunae redeuntis Eoo

Insolito cursu sideris umbra fuit;

Commoto centro tremulantia saxa dehiscunt:

Rupta cortina sancta patent populis.

Interea laetus solus subit infera Christus.

Committens tumulo membra sepulta novo.

Oplistês fortis reseravit claustra profundi;

Hostem percutiens vasa recpta tulit

Humanumque genus nolens in morte perire

Eripuit totum faucibus ex Erebi.

Te Christum colimus caeli terraque potentem:

Namque tibi soli flectitur omne genu.

Qui tantum, largire, vides quod rite rogaris

Et quod non recte rite negare soles:

Da nostro regi Karolo sua regna tenere,

Quae tu donasti partibus almigenis.

Fonte tuo manant ditantia regua per orbem:

Quod tu non dederis, quid habet ulla caro?

Indiviam miseram fratrum saevumque furorem

Digneris pacto mollificare pio.

At ne disturbent luctantia fraude maligna,

Aufer de vita semina nequitiae.

Hostiles animos paganaque rostra repellens

Da pacem populo, qui tua iura colit.

Nunc reditum Karoli celebramus carmine grato;

Post multos gemitus gaudia nostra nitent.

Qui laeti fuerant quaerentes extera regna,

Alas arripiunt, quas dedit ipsa fuga.

Atque pavor validus titubantia pectora turbans

Compellit Karolo territa dorsa dare.

Heheu quam turpis confundit corda cupido

Expulso Christo sedibus ex propriis.

O utinam, Hluduwice, tuis pax esset in oris,

Quas tibi distribuit qui regit omne simul.

Quid superare velis fratrem? Quid pellere regno?

Numquid non simili stemmate progeniti?

Cur sic conaris divinas solvere leges?

Ingratusque tuis cur aliena petis?

Quid tibi baptismus, quid sancta sollempnia missae

Occultis semper nutibus insinuant?

Numquid non praecetpa simul fraterna tenere,

Viribus ac totis vivere corde pio?

Ausculta pavidus, quid clamat summa sophia,

Quae nullum fallit dogmata vera docens:

'Si tibi molestum nolis aliunde venire,

Nullum praesumas laedere parte tua'.

Christe, tuis famulis caelestis praemia vitae

Praesta; versificos tute tuere tuos.

Poscenti domino servus sua debita solvit,

Mercedem servi sed videat dominus.

Hellinus Troasque suos cantarat Homerus,

Romuleum prolem finxerat ipse Maro;

At nos caeligenum regis pia facta canamus.

Continuo cursu quem canit orbis ovans.

Illis Iliacas flammas subitasque ruinas

Eroumque Machas dicere ludus erat;

Ast nobis Christum devicto principe mundi

Sanguine perfusum psallere dulce sonat.

Illi composito falso sub imagine veri

Fallere condocti versibus Arcadicis;

Nobis virtutem patris veramque sophiam

Ymnizare licet laudibus eximiis.

Moysarum cantus, ludos satyrasque loquaces

Ipsis usus erat plaudere per populos:

Dicta prophetarum nobis modulamine pulchro

Consona procedunt cordibus ore fide.

Nunc igitur Christi videamus summa tropea

Ac nostrae mentis sidera perspicua.

Ecce crucis lignum quadratum continet orbem.

In quo pendebat sponte sua dominus

Et verbum patris dignatum sumere carnem

In quo pro nobis hostia grata fuit.

Aspice confossas palmas humerosque pedesque,

Spinarum serto tempora cincta fero.

In medio lateris reserato fonte salutis

V

Unda lavat totum veteri peccamine mundum,

Sanguis mortales nos facit esse deos.

Binos adde reos pendentes arbore bina:

Par fuerat meritum, gratia dispar erit.

Unus cum Christo paradisi limina vidit.

Alter sulphureae mersus in ima stygis.

Eclypsis solis, lunae redeuntis Eoo

Insolito cursu sideris umbra fuit;

Commoto centro tremulantia saxa dehiscunt:

Rupta cortina sancta patent populis.

Interea laetus solus subit infera Christus.

Committens tumulo membra sepulta novo.

Oplistês fortis reseravit claustra profundi;

Hostem percutiens vasa recpta tulit

Humanumque genus nolens in morte perire

Eripuit totum faucibus ex Erebi.

Te Christum colimus caeli terraque potentem:

Namque tibi soli flectitur omne genu.

Qui tantum, largire, vides quod rite rogaris

Et quod non recte rite negare soles:

Da nostro regi Karolo sua regna tenere,

Quae tu donasti partibus almigenis.

Fonte tuo manant ditantia regua per orbem:

Quod tu non dederis, quid habet ulla caro?

Indiviam miseram fratrum saevumque furorem

Digneris pacto mollificare pio.

At ne disturbent luctantia fraude maligna,

Aufer de vita semina nequitiae.

Hostiles animos paganaque rostra repellens

Da pacem populo, qui tua iura colit.

Nunc reditum Karoli celebramus carmine grato;

Post multos gemitus gaudia nostra nitent.

Qui laeti fuerant quaerentes extera regna,

Alas arripiunt, quas dedit ipsa fuga.

Atque pavor validus titubantia pectora turbans

Compellit Karolo territa dorsa dare.

Heheu quam turpis confundit corda cupido

Expulso Christo sedibus ex propriis.

O utinam, Hluduwice, tuis pax esset in oris,

Quas tibi distribuit qui regit omne simul.

Quid superare velis fratrem? Quid pellere regno?

Numquid non simili stemmate progeniti?

Cur sic conaris divinas solvere leges?

Ingratusque tuis cur aliena petis?

Quid tibi baptismus, quid sancta sollempnia missae

Occultis semper nutibus insinuant?

Numquid non praecetpa simul fraterna tenere,

Viribus ac totis vivere corde pio?

Ausculta pavidus, quid clamat summa sophia,

Quae nullum fallit dogmata vera docens:

'Si tibi molestum nolis aliunde venire,

Nullum praesumas laedere parte tua'.

Christe, tuis famulis caelestis praemia vitae

Praesta; versificos tute tuere tuos.

Poscenti domino servus sua debita solvit,

Mercedem servi sed videat dominus.

Friday, 16 July 2010

The Aesthetics of St. Bonaventure

Another book on Bonaventure:

The Category of The Aesthetic in the Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure, by Sister Emma Jane Marie Spargo, St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: The Franciscan Institute, 1953.

Platonic concepts: the one, the true and the good, and to each of them there is a differnt kind of causality can be attributed (cf. p. 36):

the one - efficient causality

the good - final causality

the true - formal causality

And the beautiful embraces all these causes.

2) the rational structure of beauty: it is quite striking for Bonaventure. Not only does the rationality of beautiful consists in the above mentioned order and proportion, but also in the rational reflection which follows the delight which one experiences at the presence of what is beautiful. Beauty leads to love. The delight is experienced in the presence of the beautiful in a spontanious way and without reflection. Afterwards there follows an act of the intellect which inquires why these objects produce their pleasant effects and what constitutes the pleasure that result from their perception. (Hoc est autem cum quaeritur ratio pulchri, suavis et salubris; et invenitur, quod haec est proportio aequalitatis. Ratio autem aequalitatis est eadem in magnis et parvis nec extenditur dimensionibus nec succedit seu transit cum transeuntibus nec motibus alteratur). In this point St. Bonaventure differs from St. Thomas, the latter proposes that an element of grandeur is needed for an object to be considered beautiful. What makes the things beautiful is the beauty itself. Beauty, while it delights, does not fully satisfy, but leads one to seek further on, as Bonaventure wrote: "Scientia reddit opus pulcrum, voluntas reddit utile, persevarantia reddit stabile. Primum est in rationali, secundum in concupiscibili, tertium in irascibili" (De Red. Art. ad Theol. 13).

3) The Christo-centric theology of Bonaventure leads him to take scars as beautifying the body, it is also a Franciscan tradition as the Franciscans confide themselves to the Amor Pauperis Crucifixi. This Christo-centric theology is supposed by some researchers to be manifested in the depiction of Christ as the Creator, for example at the portal of Cathedral Chartres. At the entrance of Chartres Cathedral one can see: the Creator is not shown as an image of God the Father, but is Christ. There is another picture showing Christ as Creator (from a manuscript of the 13th. century):

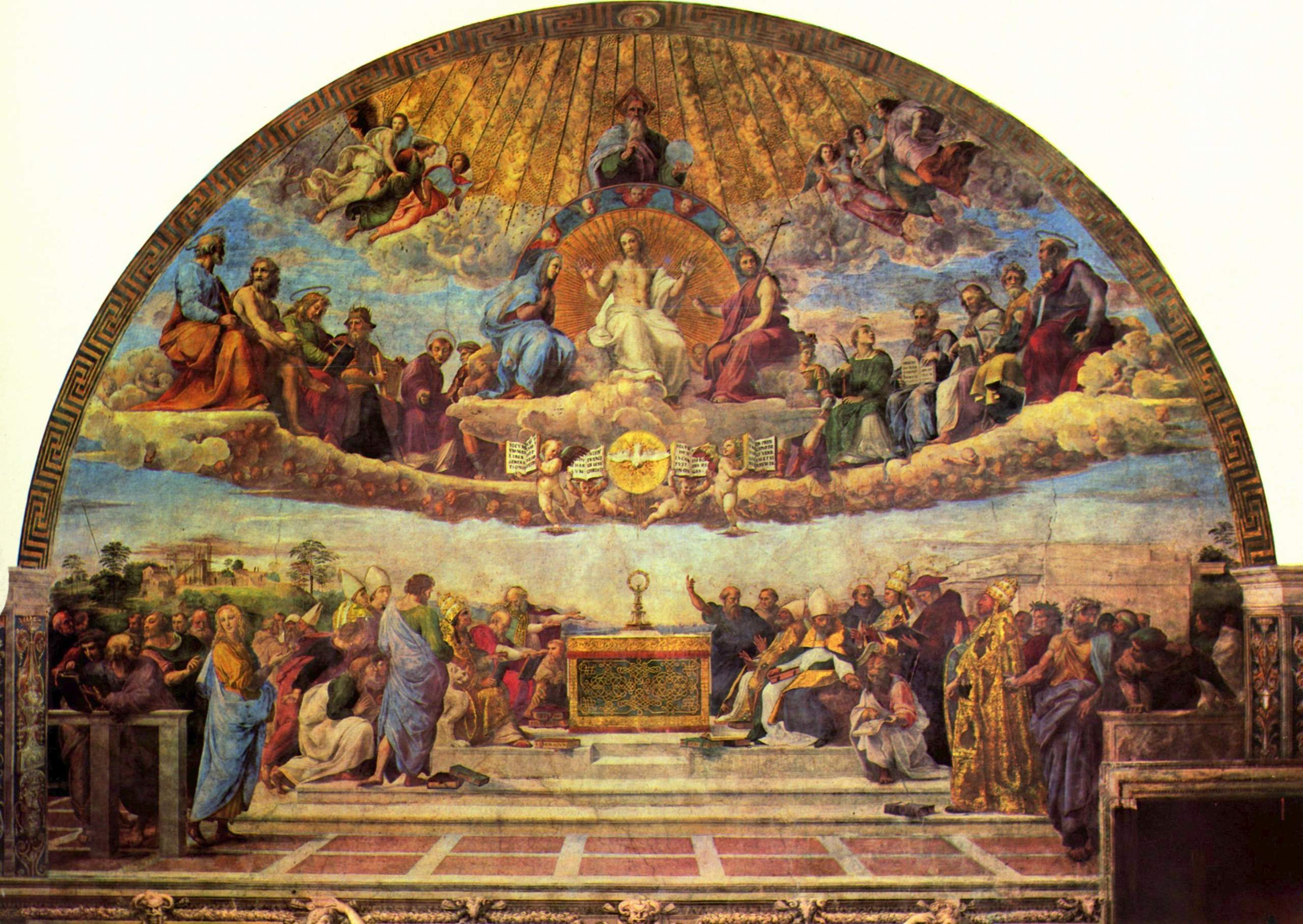

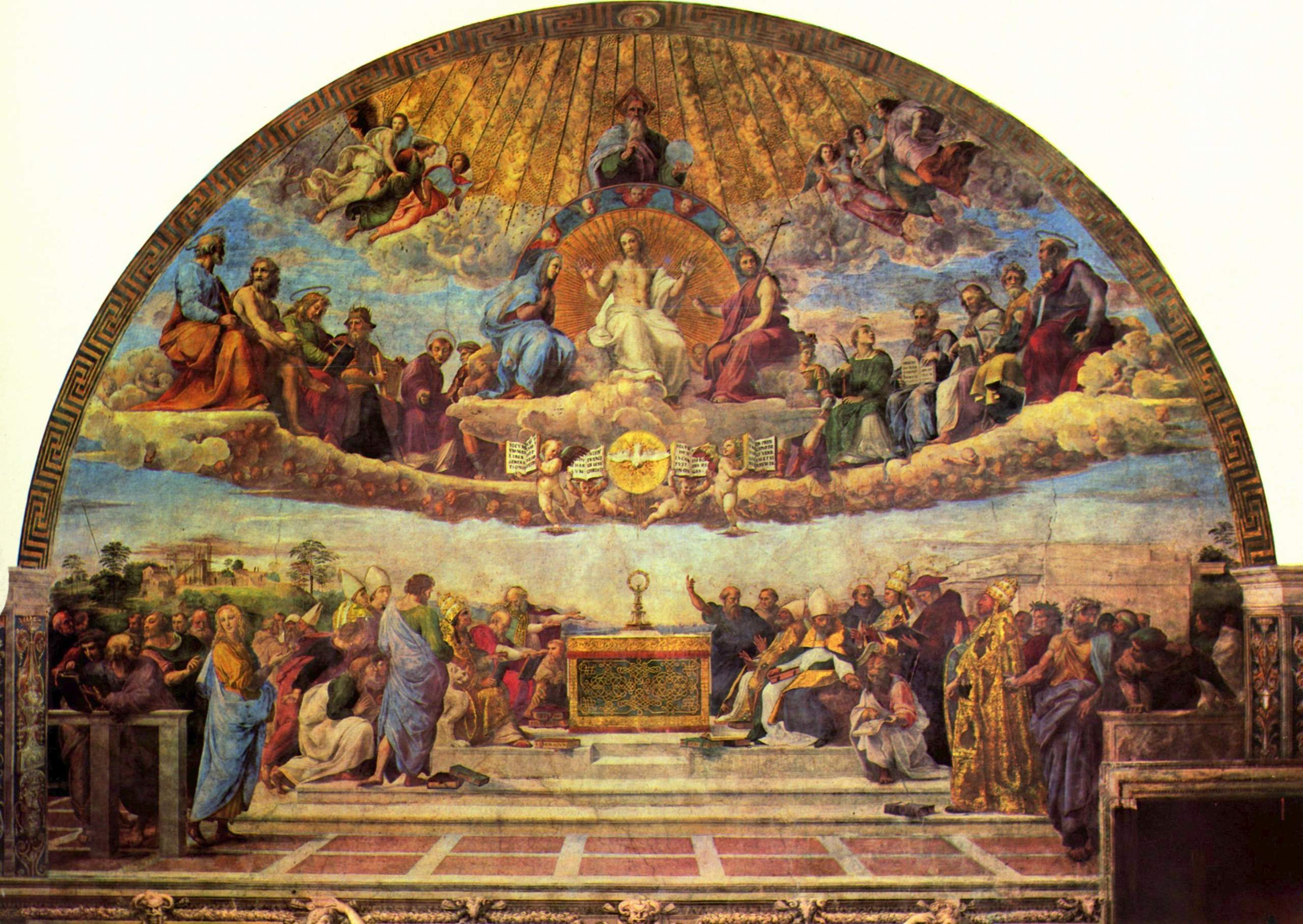

Father Boehner of the Franciscan Order pointed out, that the Frecos Stanza della Segnatura of Raphael was inspired by Franciscan thought, and that the textual source for it is the Prologue to Bonaventure's Breviloquium. In this series of frescos, we can see the Cardinal himself depicted, together with Pope Sixtus IV, who canonized him. (on the right side beneath, the one with the Cardinal's hat).

4) the natural and supernatural Beauty

Natural Beauty of the Soul: imago Dei - memoria, intellectus, voluntas - philosophical virtues; supernatural Beauty of the soul - theological virtues.

The Category of The Aesthetic in the Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure, by Sister Emma Jane Marie Spargo, St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: The Franciscan Institute, 1953.

This book, though quite good, is not such a splendid work like the Bonaventure book of our Holy Father. The author repeats too often the same ideas again and again, and doesn't develop many original insights. Nevertheless, some main ideas are quite interesting:

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

Platonic concepts: the one, the true and the good, and to each of them there is a differnt kind of causality can be attributed (cf. p. 36):

the one - efficient causality

the good - final causality

the true - formal causality

And the beautiful embraces all these causes.

2) the rational structure of beauty: it is quite striking for Bonaventure. Not only does the rationality of beautiful consists in the above mentioned order and proportion, but also in the rational reflection which follows the delight which one experiences at the presence of what is beautiful. Beauty leads to love. The delight is experienced in the presence of the beautiful in a spontanious way and without reflection. Afterwards there follows an act of the intellect which inquires why these objects produce their pleasant effects and what constitutes the pleasure that result from their perception. (Hoc est autem cum quaeritur ratio pulchri, suavis et salubris; et invenitur, quod haec est proportio aequalitatis. Ratio autem aequalitatis est eadem in magnis et parvis nec extenditur dimensionibus nec succedit seu transit cum transeuntibus nec motibus alteratur). In this point St. Bonaventure differs from St. Thomas, the latter proposes that an element of grandeur is needed for an object to be considered beautiful. What makes the things beautiful is the beauty itself. Beauty, while it delights, does not fully satisfy, but leads one to seek further on, as Bonaventure wrote: "Scientia reddit opus pulcrum, voluntas reddit utile, persevarantia reddit stabile. Primum est in rationali, secundum in concupiscibili, tertium in irascibili" (De Red. Art. ad Theol. 13).

3) The Christo-centric theology of Bonaventure leads him to take scars as beautifying the body, it is also a Franciscan tradition as the Franciscans confide themselves to the Amor Pauperis Crucifixi. This Christo-centric theology is supposed by some researchers to be manifested in the depiction of Christ as the Creator, for example at the portal of Cathedral Chartres. At the entrance of Chartres Cathedral one can see: the Creator is not shown as an image of God the Father, but is Christ. There is another picture showing Christ as Creator (from a manuscript of the 13th. century):

Father Boehner of the Franciscan Order pointed out, that the Frecos Stanza della Segnatura of Raphael was inspired by Franciscan thought, and that the textual source for it is the Prologue to Bonaventure's Breviloquium. In this series of frescos, we can see the Cardinal himself depicted, together with Pope Sixtus IV, who canonized him. (on the right side beneath, the one with the Cardinal's hat).

4) the natural and supernatural Beauty

Natural Beauty of the Soul: imago Dei - memoria, intellectus, voluntas - philosophical virtues; supernatural Beauty of the soul - theological virtues.

Labels:

Latin,

Philosophy,

Theology

Thursday, 15 July 2010

Pope Benedict on Bonaventure (His book: The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure)

A great book. Before I go into details, I want to enhance some important points and thoughts which occurred to me while reading:

1) The notion of history with an emphasis on the future in the theology of Bonaventure is quite interesting, Pope Benedict could be thinking of the Council Document "Gaudium et Spes" while writing;

2) the Notion of Tradition is interesting, against a static understanding of Tradition, this point, according to my understanding, is responsible for the "Hermeneutic of Continuity" of our Holy Father;

3) The development of the understanding of the Scripture;

On the 14th. of July, the Church celebrated the Feast Day of St. Bonaventure, the Doctor Seraphicus. Already at the age of 36 he was elected the seventh Superior General of the Franciscan Order. He doesn't belong to the most famous or the popular saints, though he was already raised to the altar on the on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the Church in the year 1588 by Pope Sixtus V. Nevertheless, Saint Bonaventure is not only a key figure in the history of philosophy and theology, his thought is even today of actuality, because his thinking is important for a better understanding of the theology of our Holy Father Benedict XVI.

Our Holy Father wrote as a young man his qualification's writing for a teaching position (Habilitationschrift) on the theology of St. Bonaventure (engl. translation by Zachary Hayes OFM, The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1971), in which the young theologian Joseph Ratzinger explored Bonaventure's attitude to Joachim of Fiores conception of history and prophecy. The abbot Joachim was a controversial figure in the Church history. He was considered by many as a Saint, though never officially approved, and his Feast Day was celebrated, unofficially, on the 29th. of May. And Dante made him immortal in the Divina Comedia, as standing at the side of St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure:

... e lucemini da lato

il Calavrese abate Gioachino

de spirito profetico dotato. (Parad., XII, 130-141)

But Joachim's teaching on the Trinity was criticised by the famous Peter Lombard, whose Sententiae was generally used as a textbook in the scholastics. Peter Lombard opined that Joachim presented a kind of Quartenitas, which took the Trinity as fourth unity besides the God Father, Son and the Holy Ghost. And some other points of Joachim's teaching were examined in year 1254, though he was never officially accused of heresy by the Church. Nevertheless, his followers, the Joachimites were condemned by Pope Alexander IV. in 1256.

In his thesis, Joseph Ratzinger takes a close look at Bonaventure's Collationes in Hexaemeron, which presents a fundamental treatment of the theology of history. Through careful textual analysis, Ratzinger shows that in difference to the traditional schema of seven ages, which goes back to Augustine (De civitate Dei ), or the schema of five ages based on the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Mt. 20, 1-16). Bonaventure offers a new schema of two ages which consists of the age of the Old Law and the New Law. Significant for Bonaventure's theology of history is also the inner-worldly, inner-historical messianic hope, while he rejects the view that with Christ the highest degree of inner-historical fulfilment is already realized so that only an eschatological hope for that which lies beyond all history is left (op. cit. 14). The future has its seeds in the past, and history is not a concatination of blind and chance happenings. With this, the rational structure of history is decisively affirmed. The real point, thus writes Ratzinger, is not the understanding of the past, but prophecy about that which is to come. But a knowledge of the past is necessary for the grasp of the future.

Though Bonaventure borrowed the two ages schema from Joachim, he did condemn the latter's idea of an eternal Gospel, which was supposed to take the place of the New Testament. And whilst Joachim expresses the idea of a new Order in which the ecclesia comtemplativa makes up the final age, while Bonaventures sees the new Order only as a fuller insight into the Scripture. In opposition to the Spirituals led by figures like Joachim and Johannes of Parma, Bonaventure stressed that Francis' own eschatological form of life could not exist as an institution in this world; "it could only be realized as a break-through of grace in the individual until such time as the God-given hour would arrive at which the world would be transformed into its final form of existence" (op. cit. 51).

"Francis is the apocalyptic angel of the seal from whom should come the final People of God, the 144,000 who are sealed. This final people of God is a community of contemplative men; in this community the form of life realized in Francis will become the general form of life. It will be the lot of this People to enjoy already in this world the peace of the seventh day which is to precede the Parousia of the Lord. [...] When this time arrives, it will be a time of contemplatio, a time of the full understanding of Scripture, and in this respect, a time of the Holy Spirit who leads us into the fullness of the truth of Jesus Christ" (op. cit. 54-55).

2. revelation: Bonaventure didn't talk of the "revelation" like we do today in the Fundamental Theology, but of "revelations". Three meanings in the works of Bonaventure: 1) In the Hexaemeron, revelatio means the unveiling of the future; 2) the hidden "mystical" meaning of Scripture; 3) that imageless unveiling of the divine reality which takes place in the mystical ascent (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite).

According to Bonaventure, the goal of Chrisitan learning is Wisdom, which can be divided into the following degrees:

sapientia multiformis - Epistle to the Ephesians

sapientia omniformis - Salomon

sapientia nulliformis - the mystic approaches in silents to the threshold of the mystery of the eternal God in the night of the intellect (Paul taught it to Timothy and Dionysius)

Bonaventure doesn't refer to the Scriptures themselves as "revelation". Instead, the revelation for him is the spiritual sense of Scripture.

Three visions (like Rupert of Deutz and St. Augustine): visio corporalis, visio spiritualis, viso intellectualis. Bonaventure holds that the content of faith is not found in the letter of Scripture but in the spiritual meaning lying behind the letter. But this view ought not to be understood as a kind of subjective actualism. because the deep meaning of Scripture is not left up to the whim of each individual. Instead, the content of the Faith "has already been objectified in part in the teachings of the Fathers and in theology so that the basic lines are accesible simple by the acceptance of the Catholic Faith. [...] Only Scripture as it is understood in faith is truly holy Scripture. Consequently, Scripture in the full sense is theology" (op. cit. 67).

Bonaventure believes that there is a gradual, historical, progressive development in the understanding of the Scripture which was in no way closed.

3) the Concept of Tradition and the Franciscan Order

According to Martin Grabmann, for Hugo of St. Victor, Scripture and the Fathers flow together into one great Scriptura Sacra. And at the time of Bonaventure, the Canon was set down for him as it stands today. But St. Francis challenged with his life according to the Sermon on the Mount this overtly statistic concept of Tradition.

4) Bonaventure in context of his time

under the influence of Rupert of Deutz (the emphasis on the future), Honorius of Autun and Anselm of Havelberg (the eschatological aspect of history).

"In contrast with Aquinas, Bonaventure expressly recognized Joachim's Old Testament exegesis and adopted it as his own. In this case, Thomas is more an Augustinian than is Bonaventure. [...] But the difference that separates Bonaventure from Joachim is greater than it may seem at first. Bascially he is in agreement with the Thomistic critique, for he also affirms a Christo-centrism. Bonaventure does not accept the notion of an age of the Holy Spirit which destroyed the central position of Christ in the Joachimite view" (op. cit. 117).

5) the Anti-Aristotelism of Bonaventure:

for a Christian understanding of time. For Aristotle, the world is eternal, which is contra the Christian teaching.

Philosophy as a "lignum scientiae boni et mali". but also as the Beast from the Abyss (Hexaemeron XVI), reason, the Harlot and the prophecy of the end of rational theology.

1) The notion of history with an emphasis on the future in the theology of Bonaventure is quite interesting, Pope Benedict could be thinking of the Council Document "Gaudium et Spes" while writing;

2) the Notion of Tradition is interesting, against a static understanding of Tradition, this point, according to my understanding, is responsible for the "Hermeneutic of Continuity" of our Holy Father;

3) The development of the understanding of the Scripture;

On the 14th. of July, the Church celebrated the Feast Day of St. Bonaventure, the Doctor Seraphicus. Already at the age of 36 he was elected the seventh Superior General of the Franciscan Order. He doesn't belong to the most famous or the popular saints, though he was already raised to the altar on the on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the Church in the year 1588 by Pope Sixtus V. Nevertheless, Saint Bonaventure is not only a key figure in the history of philosophy and theology, his thought is even today of actuality, because his thinking is important for a better understanding of the theology of our Holy Father Benedict XVI.

Our Holy Father wrote as a young man his qualification's writing for a teaching position (Habilitationschrift) on the theology of St. Bonaventure (engl. translation by Zachary Hayes OFM, The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1971), in which the young theologian Joseph Ratzinger explored Bonaventure's attitude to Joachim of Fiores conception of history and prophecy. The abbot Joachim was a controversial figure in the Church history. He was considered by many as a Saint, though never officially approved, and his Feast Day was celebrated, unofficially, on the 29th. of May. And Dante made him immortal in the Divina Comedia, as standing at the side of St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure:

... e lucemini da lato

il Calavrese abate Gioachino

de spirito profetico dotato. (Parad., XII, 130-141)

But Joachim's teaching on the Trinity was criticised by the famous Peter Lombard, whose Sententiae was generally used as a textbook in the scholastics. Peter Lombard opined that Joachim presented a kind of Quartenitas, which took the Trinity as fourth unity besides the God Father, Son and the Holy Ghost. And some other points of Joachim's teaching were examined in year 1254, though he was never officially accused of heresy by the Church. Nevertheless, his followers, the Joachimites were condemned by Pope Alexander IV. in 1256.

In his thesis, Joseph Ratzinger takes a close look at Bonaventure's Collationes in Hexaemeron, which presents a fundamental treatment of the theology of history. Through careful textual analysis, Ratzinger shows that in difference to the traditional schema of seven ages, which goes back to Augustine (De civitate Dei ), or the schema of five ages based on the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Mt. 20, 1-16). Bonaventure offers a new schema of two ages which consists of the age of the Old Law and the New Law. Significant for Bonaventure's theology of history is also the inner-worldly, inner-historical messianic hope, while he rejects the view that with Christ the highest degree of inner-historical fulfilment is already realized so that only an eschatological hope for that which lies beyond all history is left (op. cit. 14). The future has its seeds in the past, and history is not a concatination of blind and chance happenings. With this, the rational structure of history is decisively affirmed. The real point, thus writes Ratzinger, is not the understanding of the past, but prophecy about that which is to come. But a knowledge of the past is necessary for the grasp of the future.

Though Bonaventure borrowed the two ages schema from Joachim, he did condemn the latter's idea of an eternal Gospel, which was supposed to take the place of the New Testament. And whilst Joachim expresses the idea of a new Order in which the ecclesia comtemplativa makes up the final age, while Bonaventures sees the new Order only as a fuller insight into the Scripture. In opposition to the Spirituals led by figures like Joachim and Johannes of Parma, Bonaventure stressed that Francis' own eschatological form of life could not exist as an institution in this world; "it could only be realized as a break-through of grace in the individual until such time as the God-given hour would arrive at which the world would be transformed into its final form of existence" (op. cit. 51).

"Francis is the apocalyptic angel of the seal from whom should come the final People of God, the 144,000 who are sealed. This final people of God is a community of contemplative men; in this community the form of life realized in Francis will become the general form of life. It will be the lot of this People to enjoy already in this world the peace of the seventh day which is to precede the Parousia of the Lord. [...] When this time arrives, it will be a time of contemplatio, a time of the full understanding of Scripture, and in this respect, a time of the Holy Spirit who leads us into the fullness of the truth of Jesus Christ" (op. cit. 54-55).

2. revelation: Bonaventure didn't talk of the "revelation" like we do today in the Fundamental Theology, but of "revelations". Three meanings in the works of Bonaventure: 1) In the Hexaemeron, revelatio means the unveiling of the future; 2) the hidden "mystical" meaning of Scripture; 3) that imageless unveiling of the divine reality which takes place in the mystical ascent (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite).

According to Bonaventure, the goal of Chrisitan learning is Wisdom, which can be divided into the following degrees:

sapientia multiformis - Epistle to the Ephesians

sapientia omniformis - Salomon

sapientia nulliformis - the mystic approaches in silents to the threshold of the mystery of the eternal God in the night of the intellect (Paul taught it to Timothy and Dionysius)

Bonaventure doesn't refer to the Scriptures themselves as "revelation". Instead, the revelation for him is the spiritual sense of Scripture.

Three visions (like Rupert of Deutz and St. Augustine): visio corporalis, visio spiritualis, viso intellectualis. Bonaventure holds that the content of faith is not found in the letter of Scripture but in the spiritual meaning lying behind the letter. But this view ought not to be understood as a kind of subjective actualism. because the deep meaning of Scripture is not left up to the whim of each individual. Instead, the content of the Faith "has already been objectified in part in the teachings of the Fathers and in theology so that the basic lines are accesible simple by the acceptance of the Catholic Faith. [...] Only Scripture as it is understood in faith is truly holy Scripture. Consequently, Scripture in the full sense is theology" (op. cit. 67).

Bonaventure believes that there is a gradual, historical, progressive development in the understanding of the Scripture which was in no way closed.

3) the Concept of Tradition and the Franciscan Order

According to Martin Grabmann, for Hugo of St. Victor, Scripture and the Fathers flow together into one great Scriptura Sacra. And at the time of Bonaventure, the Canon was set down for him as it stands today. But St. Francis challenged with his life according to the Sermon on the Mount this overtly statistic concept of Tradition.

4) Bonaventure in context of his time

under the influence of Rupert of Deutz (the emphasis on the future), Honorius of Autun and Anselm of Havelberg (the eschatological aspect of history).

"In contrast with Aquinas, Bonaventure expressly recognized Joachim's Old Testament exegesis and adopted it as his own. In this case, Thomas is more an Augustinian than is Bonaventure. [...] But the difference that separates Bonaventure from Joachim is greater than it may seem at first. Bascially he is in agreement with the Thomistic critique, for he also affirms a Christo-centrism. Bonaventure does not accept the notion of an age of the Holy Spirit which destroyed the central position of Christ in the Joachimite view" (op. cit. 117).

5) the Anti-Aristotelism of Bonaventure:

for a Christian understanding of time. For Aristotle, the world is eternal, which is contra the Christian teaching.

Philosophy as a "lignum scientiae boni et mali". but also as the Beast from the Abyss (Hexaemeron XVI), reason, the Harlot and the prophecy of the end of rational theology.

Labels:

Pope Benedict,

Theology

Monday, 12 July 2010

Carpe diem!

Today I picked up occasionally the edition of Horace's Odes and Epodes, edited by the Latinist Bernard Kytzler for students (Reclam 2000). Though I found initially Horace's world foreign to me, his carmen I, XI which I happened to read today struck me directly in the heart. It is written in Asclepiadeus maior (---uu- | -uu- | -uu-uu). The phrase "carpe diem" emerges in the last verse. An outworn phrase used to urge people to enjoy the life. But indeed I find it not so jolly as it seems. If you don't think of the nearing death, you won't be in need of urging yourself to grasp the fleeing day. How is it possible to get hold of the time, I ask you mate? Especially the word "pati" in the third verse betrayed the sadness hidden behind the seemingly careless tone of the poet. And the first lines of this poem begin directly with the thought on Death. It reminds me of the poems of the baroque era in which the poet urges his beloved woman not to hesitate to accept his love, because the snow of her shoulders will be ashes tomorrow.

Horatius carmen I, XI:

Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi

finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios

temptaris numeros. ut melius, quidquid erit, pati.

seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam,

quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare

Tyrrhenum: sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi

spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas: carpe diem quam minimum credula postero.

Horatius carmen I, XI:

Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi

finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios

temptaris numeros. ut melius, quidquid erit, pati.

seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam,

quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare

Tyrrhenum: sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi

spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas: carpe diem quam minimum credula postero.

Labels:

Latin

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Cor, quare me flere facis?

Cor stultum, putas quod iste vir me puellam miseram olim amavit? Ego nescio utrum hoc verum est. Nec audeo interrogare me ipsum utrum. Solum flere volo. Mens mea, mihi nullam responsionem da, cor meum franges.

Mens, cor, cur me affligitis? Amo, et amare desistere non possum. Umbram amo, animam pulchram amo. Mens, noli docere me quid prudens est, quia timeo me numquam somniaturam esse. Sed somniare volo. Cor, quare me flere facis? Somnium istud bellulum est. Cor, quare fleo quamvis somnio? Fleo veraciter in somnio.

Cor meum iam fractum est.

Mens, cor, cur me affligitis? Amo, et amare desistere non possum. Umbram amo, animam pulchram amo. Mens, noli docere me quid prudens est, quia timeo me numquam somniaturam esse. Sed somniare volo. Cor, quare me flere facis? Somnium istud bellulum est. Cor, quare fleo quamvis somnio? Fleo veraciter in somnio.

Cor meum iam fractum est.

Saturday, 10 July 2010

Eriugena's Immediate Influence (Note on the same book of O'Meara, Chapter 11)

In the Gesta episcoporum Autissiodorensium one reads that Wicbald (Guibaud), Bishop of Auxerre (879), was a disciple of Eriugena.

Eriugena was in the palace school of Charles the Bald. Indications show that he remained there from the early fifties until perhaps the late seventies of the ninth century. But it is unknown where this palace school was. It might have been in Laon, or in the neighbourhood, at Quierzy or Compiègne.

Two persons are especially important: Wulfad and Winibert. The Periphyseon was dedicated to Wulfad. Wulfad was a cleric of Reims, ordained by Ebbon but unrecognized by Hincmar, he became tutor of Charles the Bald's son Carloman (854-60), than abbot of Montierender (855-6), abbot of Saint-Médard at Soisson (858), abbot of Rebais (after 860), finally archbishop of Bourges. *(very important fact!):

"A list of some thirty-one books in his library show that it contained many of the same Greek authors as are found in Laon. It also contained Eriugena's translation of the Pseudo-Dionysius and the Quaestiones ad Thalassium of Maximus the Confessor as well as the Periphyseon. The list itself was written on the penultimate leaf of a volume containing Eriugena's translation of Maximus's Ambigua" (p. 199).

Manuscript Laon 24 contains a letter to a certain dominus Winibertus (according to J.J. Contreni the abbot of Schuttern in the diocese of Strasbourg) in which Eriugena expresses regret that he and Winibert had been separated so that their work on Martinaus Capella had become difficult.

Martin the Irishman, who taught at the cathedral school in Laon, belonged to the group of Irish in Laon whom Eriugena knew there. Martin used poems of Eriugena in his handbook MS Laon 444.

MS Paris BN lat. 10307 contains extracts from the Greek-Latin glossary of Martin and also a verse concerning Fergus and two distichs identified as Eriugena's by C. Leonardi.

Fergus was a close friend of Sedulius. Both Sedulius and Fergus are metioned in the marginalia of the ninth-century Codex Bernensis 363 along with Eriugena and some twelve other Irish contemparies. Also included in the marginalia are Gottschalk, Hincmar, and Ratramnus. Authors referred to in the MS are Donatus, Fulgentius, Hadrian, Honoratus, Isidore, Martinaus Capella, Priscian, Sergius, and Virgilius. The combination of all these naems of Eriugena's contemporaries suggest a common interest in the themes associated with the authors detailed. The name of Eriugena is entered over and over again aomong the marginalia of this manuscript, opposite passages relevant to Eriugena's teaching, and it is clear that the glossators knew the Periphyseon. Fergus, described as a grammaticus, is probably also to be associated with Eriugena and Bishop Pardulus of Laon in relation to a medicament recommended for the removal of unwanted hair (curious thing).

Two pupils of Eriugena: Elias, an Irishman, later bishop of Angoulême (861-75) and Wicbald, later bishop of Auxerre (879-87). In biblical glosses attributed to Eriugena some fifty words in Old Irish are used as glosses on the Old Testament.

Others who were influenced by him: Almannus of Hautvillers and Hucbald of St. Amand, the latter made a florilegium of Eriugenan thoughts.

Heiric of Auxerre, author of Life of St Germanus, Collectanea, Homiliary. He borrowed from Eriugena in his Life of St. Germanus and Homiliary. In the Life of St. Germanus: the same language, the same themes, the same insertion of occasional Greek words or verses. Also his Homiliaryis heavily indebted to Eriugena's Homily on the Prolouge to St. John's Gospel. Heiric was in his Life of St. Germanus indebted to Periphyseon I-III. The Homily reveals that he knew Periphyseon IV and V as well.

Three ancient texts were glossed by those engaged in teaching and learning: Martianus Capella's De nuptiis (glossed by Eriugena and Marin); Boethius's Opuscula sacra and the Categoriae decem (a worled attributed to Augustine and used extensively by Eriugena in the first book of Periphyseon).

Heiric might have become a follower of Eriugena through his teacher Remigius of Auxerre Remigius might have been born in Ireland in the early forties. He is first identified as a monk at the abbey of St-Germain at Auxerre, wrote a commentary on the Consolatio of Boethius and a commentary on Martianus Capella.