The Category of The Aesthetic in the Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure, by Sister Emma Jane Marie Spargo, St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: The Franciscan Institute, 1953.

This book, though quite good, is not such a splendid work like the Bonaventure book of our Holy Father. The author repeats too often the same ideas again and again, and doesn't develop many original insights. Nevertheless, some main ideas are quite interesting:

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

Platonic concepts: the one, the true and the good, and to each of them there is a differnt kind of causality can be attributed (cf. p. 36):

the one - efficient causality

the good - final causality

the true - formal causality

And the beautiful embraces all these causes.

2) the rational structure of beauty: it is quite striking for Bonaventure. Not only does the rationality of beautiful consists in the above mentioned order and proportion, but also in the rational reflection which follows the delight which one experiences at the presence of what is beautiful. Beauty leads to love. The delight is experienced in the presence of the beautiful in a spontanious way and without reflection. Afterwards there follows an act of the intellect which inquires why these objects produce their pleasant effects and what constitutes the pleasure that result from their perception. (Hoc est autem cum quaeritur ratio pulchri, suavis et salubris; et invenitur, quod haec est proportio aequalitatis. Ratio autem aequalitatis est eadem in magnis et parvis nec extenditur dimensionibus nec succedit seu transit cum transeuntibus nec motibus alteratur). In this point St. Bonaventure differs from St. Thomas, the latter proposes that an element of grandeur is needed for an object to be considered beautiful. What makes the things beautiful is the beauty itself. Beauty, while it delights, does not fully satisfy, but leads one to seek further on, as Bonaventure wrote: "Scientia reddit opus pulcrum, voluntas reddit utile, persevarantia reddit stabile. Primum est in rationali, secundum in concupiscibili, tertium in irascibili" (De Red. Art. ad Theol. 13).

3) The Christo-centric theology of Bonaventure leads him to take scars as beautifying the body, it is also a Franciscan tradition as the Franciscans confide themselves to the Amor Pauperis Crucifixi. This Christo-centric theology is supposed by some researchers to be manifested in the depiction of Christ as the Creator, for example at the portal of Cathedral Chartres. At the entrance of Chartres Cathedral one can see: the Creator is not shown as an image of God the Father, but is Christ. There is another picture showing Christ as Creator (from a manuscript of the 13th. century):

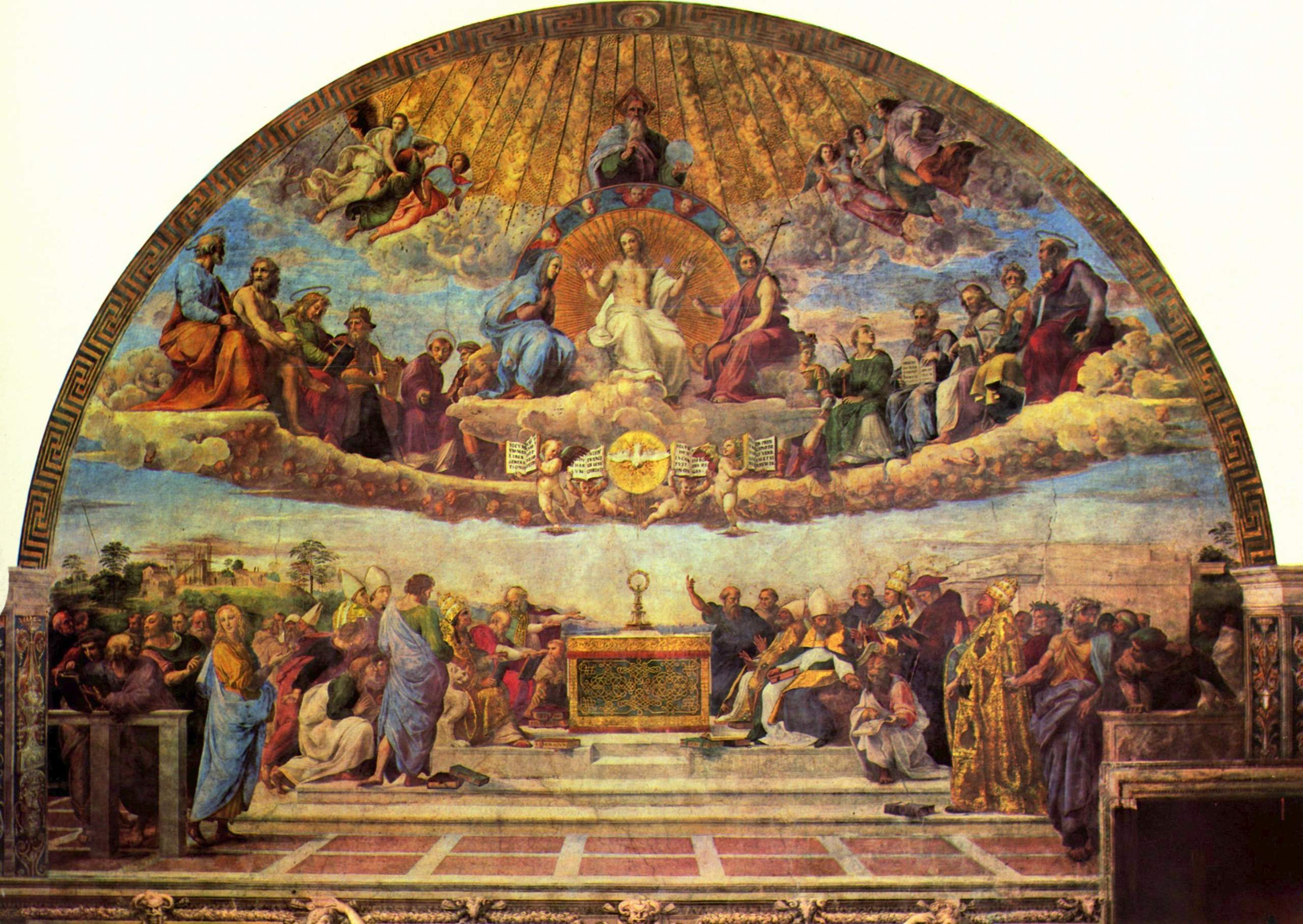

Father Boehner of the Franciscan Order pointed out, that the Frecos Stanza della Segnatura of Raphael was inspired by Franciscan thought, and that the textual source for it is the Prologue to Bonaventure's Breviloquium. In this series of frescos, we can see the Cardinal himself depicted, together with Pope Sixtus IV, who canonized him. (on the right side beneath, the one with the Cardinal's hat).

4) the natural and supernatural Beauty

Natural Beauty of the Soul: imago Dei - memoria, intellectus, voluntas - philosophical virtues; supernatural Beauty of the soul - theological virtues.

No comments:

Post a Comment