(Chapter 4) The Sermon on the Mountain is a passage which is often misused by the modernists to show that nothing is needed to achieve the salvation, no study, no observation of the laws, only a simple mind suffices. And liberal theologians tend to see this sermon as an abolishment of the Old Law, including the Decalogue.

Pope Benedict shows us that not an iota of the Old Law can be abolished, and tells us what the real meaning of this passage is. What is striking for me is how Pope Benedict shows the continuity between the Sermon on the Mountain and the Old Testament, especially the Psalms. It is also very interesting that he mentions on many places his good friend Rabbi Neusner. Thus, the liberal thesis that the Sermon on the Mountain presents a new Ethics and abolish the old Ethics of OT is refuted. And with "the poor" mentioned in the sermon are not meant impoverished people, as poverty doesn't lead to salvation, but those who are poor before God, that is, those, who don't boast of what they have done. The Holy Father cites a sentence of Therese of Lisieux: "I will stand before God with empty hands and keep them open". It means, we open our hands to receive the Grace of the Lord. The poor are also those who decide to abandon earthly comfort to follow the example of Christ, like Francis of Assisi did.

The Sermon on the Mountain, thus Pope Benedict, is a hidden Christology: as God took the flesh of man and died for our sake. So the Sermon on the Mountain tells us how to be the true imitator of Christ: to love, and that means to abandon every kind of egoism. And Pope Benedict wrote: "in opposite to the alluring glamour of Nietzsche's picture of man this way (of imitation Christi) appears poor, but it is the real way of life to ascend, only on the way of love the richness of life and the magnitude of human vocation become available".

In the second part of this chapter Pope Benedict tells us that according to the Jewish Tradition, the Messiah is supposed to bring his own "Torah". So the question is raised again: do the new laws substitute the old ones? The answer of Pope Benedict is: they don't abolish the old laws, but fulfil them. A very interesting passage which our Pope quotes from the book of Rabbi Neusner is: Jesus has, in comparison to the prophets, not a single new law! Jesus said only, come and follow me (Mt. 19, 20). And that is the reason why Rabbi Neusner decides that he remains in the Jewish Religion, because Rabbi Neusner finds that to follow Jesus will be contrary to the first (to honour God alone and to keep Sabbath) and the fourth (to honour father and mother) commandment. Pope Benedict shows that these commandments are fulfilled in the social teachings of the Church. And Pope Benedict shows also that in the Torah Israel is not only for its own people there, but is to become the light of all people in the world. The aim of the Holy Father is, as I see it, to show that Jesus Christ stands in the continuity with the OT, though he brought very new and revolutionary teachings. But his teachings can also be found in the inner structure of the Torah.

This approach of our Holy Father to the NT is very interesting. It is not only in the hermeneutic tradition of the analogical reading, but also in a new sense as he is using the Jewish Tradition of Bible reading to support our Christian teachings. It will not only teach us to have more respect and insight for the Jewish Tradition which is in part also ours, but can also be useful to explain to the Jews what Christianity is, and even persuade some of them more easily, as the Scripture is central for the Jewish Religion.

Saturday, 31 July 2010

Monday, 19 July 2010

The Reception of Homer in the Caroligian Renaissance?

I know that Homer was not read during the most time of the medium aevum. Greek was seldom studied. And as far as I know, there were no translations of Homer's Iliad and Odysseus. But it astonishes me to read that during the Carolingian Renaissance students were to read Homer. Well, at that time, Greek was still studied. Even Hincmar of Reims translated the Pseudo-Dionysius as well as John Scottus Eriugena. But still one expects little that they did read Homer. Did they learn from Homer's works through a second hand source, or was Homer read in original? This question I still have to pursuit. But it astonishes one not little when one reads from the classic allusions in a Latin poem by Eriugena (very long, typed according to the MGH edition, there nr. 2). But it doesn't show that he did read Homer himself. This poems goes on very quickly to the praise of the Cross and Christus. Eriugena wants to show that the Christian Reign is more glorious than the ancient reigns:

Hellinus Troasque suos cantarat Homerus,

Romuleum prolem finxerat ipse Maro;

At nos caeligenum regis pia facta canamus.

Continuo cursu quem canit orbis ovans.

Illis Iliacas flammas subitasque ruinas

Eroumque Machas dicere ludus erat;

Ast nobis Christum devicto principe mundi

Sanguine perfusum psallere dulce sonat.

Illi composito falso sub imagine veri

Fallere condocti versibus Arcadicis;

Nobis virtutem patris veramque sophiam

Ymnizare licet laudibus eximiis.

Moysarum cantus, ludos satyrasque loquaces

Ipsis usus erat plaudere per populos:

Dicta prophetarum nobis modulamine pulchro

Consona procedunt cordibus ore fide.

Nunc igitur Christi videamus summa tropea

Ac nostrae mentis sidera perspicua.

Ecce crucis lignum quadratum continet orbem.

In quo pendebat sponte sua dominus

Et verbum patris dignatum sumere carnem

In quo pro nobis hostia grata fuit.

Aspice confossas palmas humerosque pedesque,

Spinarum serto tempora cincta fero.

In medio lateris reserato fonte salutis

Ves haustus, sanguis et unda, fluut.

Unda lavat totum veteri peccamine mundum,

Sanguis mortales nos facit esse deos.

Binos adde reos pendentes arbore bina:

Par fuerat meritum, gratia dispar erit.

Unus cum Christo paradisi limina vidit.

Alter sulphureae mersus in ima stygis.

Eclypsis solis, lunae redeuntis Eoo

Insolito cursu sideris umbra fuit;

Commoto centro tremulantia saxa dehiscunt:

Rupta cortina sancta patent populis.

Interea laetus solus subit infera Christus.

Committens tumulo membra sepulta novo.

Oplistês fortis reseravit claustra profundi;

Hostem percutiens vasa recpta tulit

Humanumque genus nolens in morte perire

Eripuit totum faucibus ex Erebi.

Te Christum colimus caeli terraque potentem:

Namque tibi soli flectitur omne genu.

Qui tantum, largire, vides quod rite rogaris

Et quod non recte rite negare soles:

Da nostro regi Karolo sua regna tenere,

Quae tu donasti partibus almigenis.

Fonte tuo manant ditantia regua per orbem:

Quod tu non dederis, quid habet ulla caro?

Indiviam miseram fratrum saevumque furorem

Digneris pacto mollificare pio.

At ne disturbent luctantia fraude maligna,

Aufer de vita semina nequitiae.

Hostiles animos paganaque rostra repellens

Da pacem populo, qui tua iura colit.

Nunc reditum Karoli celebramus carmine grato;

Post multos gemitus gaudia nostra nitent.

Qui laeti fuerant quaerentes extera regna,

Alas arripiunt, quas dedit ipsa fuga.

Atque pavor validus titubantia pectora turbans

Compellit Karolo territa dorsa dare.

Heheu quam turpis confundit corda cupido

Expulso Christo sedibus ex propriis.

O utinam, Hluduwice, tuis pax esset in oris,

Quas tibi distribuit qui regit omne simul.

Quid superare velis fratrem? Quid pellere regno?

Numquid non simili stemmate progeniti?

Cur sic conaris divinas solvere leges?

Ingratusque tuis cur aliena petis?

Quid tibi baptismus, quid sancta sollempnia missae

Occultis semper nutibus insinuant?

Numquid non praecetpa simul fraterna tenere,

Viribus ac totis vivere corde pio?

Ausculta pavidus, quid clamat summa sophia,

Quae nullum fallit dogmata vera docens:

'Si tibi molestum nolis aliunde venire,

Nullum praesumas laedere parte tua'.

Christe, tuis famulis caelestis praemia vitae

Praesta; versificos tute tuere tuos.

Poscenti domino servus sua debita solvit,

Mercedem servi sed videat dominus.

Hellinus Troasque suos cantarat Homerus,

Romuleum prolem finxerat ipse Maro;

At nos caeligenum regis pia facta canamus.

Continuo cursu quem canit orbis ovans.

Illis Iliacas flammas subitasque ruinas

Eroumque Machas dicere ludus erat;

Ast nobis Christum devicto principe mundi

Sanguine perfusum psallere dulce sonat.

Illi composito falso sub imagine veri

Fallere condocti versibus Arcadicis;

Nobis virtutem patris veramque sophiam

Ymnizare licet laudibus eximiis.

Moysarum cantus, ludos satyrasque loquaces

Ipsis usus erat plaudere per populos:

Dicta prophetarum nobis modulamine pulchro

Consona procedunt cordibus ore fide.

Nunc igitur Christi videamus summa tropea

Ac nostrae mentis sidera perspicua.

Ecce crucis lignum quadratum continet orbem.

In quo pendebat sponte sua dominus

Et verbum patris dignatum sumere carnem

In quo pro nobis hostia grata fuit.

Aspice confossas palmas humerosque pedesque,

Spinarum serto tempora cincta fero.

In medio lateris reserato fonte salutis

V

Unda lavat totum veteri peccamine mundum,

Sanguis mortales nos facit esse deos.

Binos adde reos pendentes arbore bina:

Par fuerat meritum, gratia dispar erit.

Unus cum Christo paradisi limina vidit.

Alter sulphureae mersus in ima stygis.

Eclypsis solis, lunae redeuntis Eoo

Insolito cursu sideris umbra fuit;

Commoto centro tremulantia saxa dehiscunt:

Rupta cortina sancta patent populis.

Interea laetus solus subit infera Christus.

Committens tumulo membra sepulta novo.

Oplistês fortis reseravit claustra profundi;

Hostem percutiens vasa recpta tulit

Humanumque genus nolens in morte perire

Eripuit totum faucibus ex Erebi.

Te Christum colimus caeli terraque potentem:

Namque tibi soli flectitur omne genu.

Qui tantum, largire, vides quod rite rogaris

Et quod non recte rite negare soles:

Da nostro regi Karolo sua regna tenere,

Quae tu donasti partibus almigenis.

Fonte tuo manant ditantia regua per orbem:

Quod tu non dederis, quid habet ulla caro?

Indiviam miseram fratrum saevumque furorem

Digneris pacto mollificare pio.

At ne disturbent luctantia fraude maligna,

Aufer de vita semina nequitiae.

Hostiles animos paganaque rostra repellens

Da pacem populo, qui tua iura colit.

Nunc reditum Karoli celebramus carmine grato;

Post multos gemitus gaudia nostra nitent.

Qui laeti fuerant quaerentes extera regna,

Alas arripiunt, quas dedit ipsa fuga.

Atque pavor validus titubantia pectora turbans

Compellit Karolo territa dorsa dare.

Heheu quam turpis confundit corda cupido

Expulso Christo sedibus ex propriis.

O utinam, Hluduwice, tuis pax esset in oris,

Quas tibi distribuit qui regit omne simul.

Quid superare velis fratrem? Quid pellere regno?

Numquid non simili stemmate progeniti?

Cur sic conaris divinas solvere leges?

Ingratusque tuis cur aliena petis?

Quid tibi baptismus, quid sancta sollempnia missae

Occultis semper nutibus insinuant?

Numquid non praecetpa simul fraterna tenere,

Viribus ac totis vivere corde pio?

Ausculta pavidus, quid clamat summa sophia,

Quae nullum fallit dogmata vera docens:

'Si tibi molestum nolis aliunde venire,

Nullum praesumas laedere parte tua'.

Christe, tuis famulis caelestis praemia vitae

Praesta; versificos tute tuere tuos.

Poscenti domino servus sua debita solvit,

Mercedem servi sed videat dominus.

Friday, 16 July 2010

The Aesthetics of St. Bonaventure

Another book on Bonaventure:

The Category of The Aesthetic in the Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure, by Sister Emma Jane Marie Spargo, St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: The Franciscan Institute, 1953.

Platonic concepts: the one, the true and the good, and to each of them there is a differnt kind of causality can be attributed (cf. p. 36):

the one - efficient causality

the good - final causality

the true - formal causality

And the beautiful embraces all these causes.

2) the rational structure of beauty: it is quite striking for Bonaventure. Not only does the rationality of beautiful consists in the above mentioned order and proportion, but also in the rational reflection which follows the delight which one experiences at the presence of what is beautiful. Beauty leads to love. The delight is experienced in the presence of the beautiful in a spontanious way and without reflection. Afterwards there follows an act of the intellect which inquires why these objects produce their pleasant effects and what constitutes the pleasure that result from their perception. (Hoc est autem cum quaeritur ratio pulchri, suavis et salubris; et invenitur, quod haec est proportio aequalitatis. Ratio autem aequalitatis est eadem in magnis et parvis nec extenditur dimensionibus nec succedit seu transit cum transeuntibus nec motibus alteratur). In this point St. Bonaventure differs from St. Thomas, the latter proposes that an element of grandeur is needed for an object to be considered beautiful. What makes the things beautiful is the beauty itself. Beauty, while it delights, does not fully satisfy, but leads one to seek further on, as Bonaventure wrote: "Scientia reddit opus pulcrum, voluntas reddit utile, persevarantia reddit stabile. Primum est in rationali, secundum in concupiscibili, tertium in irascibili" (De Red. Art. ad Theol. 13).

3) The Christo-centric theology of Bonaventure leads him to take scars as beautifying the body, it is also a Franciscan tradition as the Franciscans confide themselves to the Amor Pauperis Crucifixi. This Christo-centric theology is supposed by some researchers to be manifested in the depiction of Christ as the Creator, for example at the portal of Cathedral Chartres. At the entrance of Chartres Cathedral one can see: the Creator is not shown as an image of God the Father, but is Christ. There is another picture showing Christ as Creator (from a manuscript of the 13th. century):

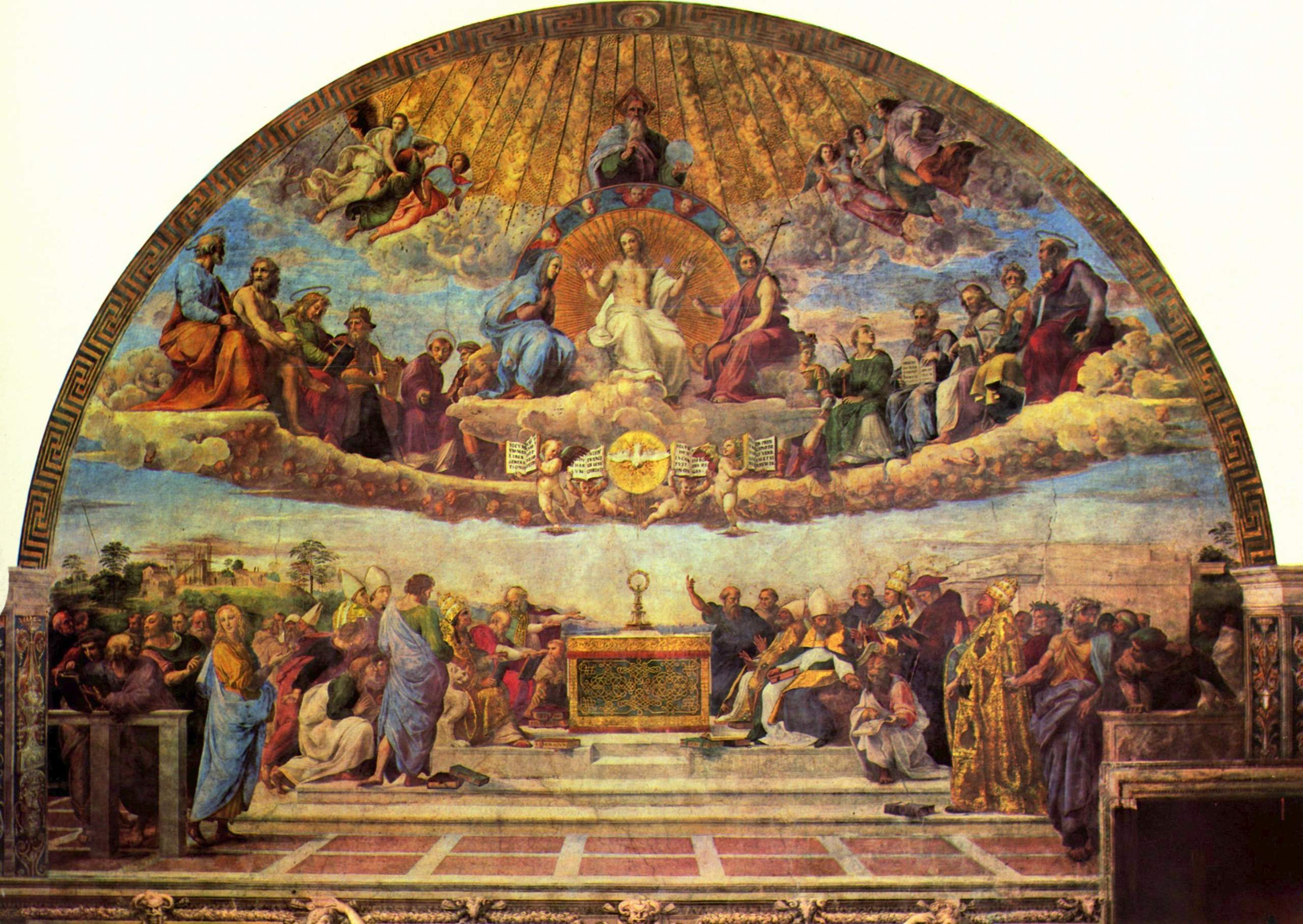

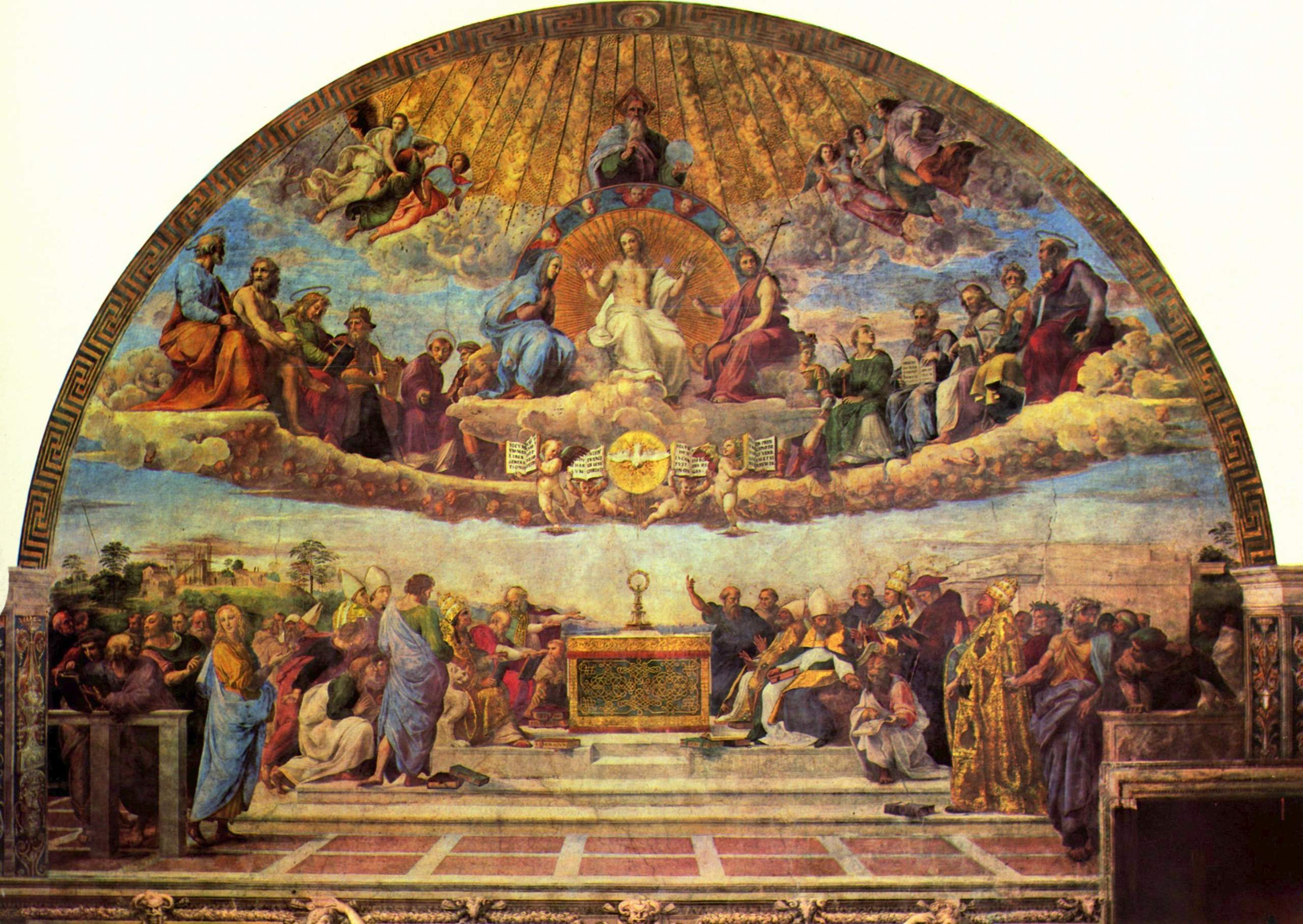

Father Boehner of the Franciscan Order pointed out, that the Frecos Stanza della Segnatura of Raphael was inspired by Franciscan thought, and that the textual source for it is the Prologue to Bonaventure's Breviloquium. In this series of frescos, we can see the Cardinal himself depicted, together with Pope Sixtus IV, who canonized him. (on the right side beneath, the one with the Cardinal's hat).

4) the natural and supernatural Beauty

Natural Beauty of the Soul: imago Dei - memoria, intellectus, voluntas - philosophical virtues; supernatural Beauty of the soul - theological virtues.

The Category of The Aesthetic in the Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure, by Sister Emma Jane Marie Spargo, St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: The Franciscan Institute, 1953.

This book, though quite good, is not such a splendid work like the Bonaventure book of our Holy Father. The author repeats too often the same ideas again and again, and doesn't develop many original insights. Nevertheless, some main ideas are quite interesting:

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

1) The optimism of Bonaventure and the positive attitude to the sensual world. Everything, that is, is beautiful and good. And the world is a book written by God, with his signature in it and hidden signs which could lead us to know God himself. This idea is not an uncommon one, nor is it new. The Irish theologian John Scot Eriugena already put forward a similar idea. That Bonaventure happened to concur with Eriugena, must be due to the Pseudo-Dionyius Areopagita renaissance in the thirteenth century, who inspired greatly Eriugena. In the system of Bonaventure, the transcendence is not totally separated from our sensual world. Instead, the world is a symbol of the thought of God before the creation, which was brought to actuality through the Son. The Divine Idea is hidden within the created world, which is actually an immense book written by God. And Bonaventure takes the Cosmos as a whole, quite in Platonic tradition. This can be seen in the Exemplarism of the Augustinian tradition. For Bonaventure there is a triune structure: Emantion - Exemplarism - Illumination The son emanates from the Father through a natural mode, the Divine wisdom knows everything, is the ground of knowledge. It is called light and mirror, and the book of life (Breviloquium I, 8, 2). It is the Exemplar of all creatures.

And the beauty of the Cosmos consists, not surprisingly, as the Platonics already teach, in the order and harmony between its parts. This idea is manifested in the Gothics of the 13th. century, in which Cathedrals were built according to a rational and systematic plan, and sculptures were cast as ideal of men and women, quite in contrast to the realism of the late medieval time. What is highly interesting is that 'beautiful' is taken by Bonaventure as a fourth transcendal (the other three being: unum, verum, bonum, as Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason still mentions). Transcendals are concepts which can be used to describe everything, which is. So the optism is really striking. I don't think the Platonic tradition teaches this doctrine. But Sister Spargo mentions Pseudo-Dinonysius Areopagite as the source of this thought. Nevertheless, some Franciscans already thought in this way, for example Thomas of York, Robert of Grosseteste, and John de la Rochelle.

In his Commentarium in libro Sententiarum St. Bonaventure says that "whatever possesses being will likewise possess a certain form, and everything that possesses form will possess beauty also as a necessary consequent following upon the form that gives it being" (p. 34). He refers to the etymology of the word formosa: Omne quod est ens, habet aliquam formam; omne autem quod habet aliquam formam, habet pulchritudinem (II 34, 2, 3, 6). Everything that is, is also good, and everything that is, is also beautiful. All good and all beauty have their source in the goodness of God: Omne bonum et pulchrum est a Deo bono; sed omnia visibilia bona sunt et pulcra (II 1, 1, 2, 1). The beauty is the proportion or harmony (congruentia), and there is an interior and an exterior beauty. This idea can be traced back to the Book of Wisdom: in the numero, pondere, mensura consist the habitudines. There are two trinities regarding the relation of one creature to another: one, taken from Dionysius: substantia, virtus et operation, the other is taken from Augustine: quo, constat, quo congruit, quo discernitur. For St. Bonaventure, as for St. Augustine, matter is not pure privation or potency, but contains the first and all prevading substantial form of light. According to St. Augustine matter has modum, speciem and ordinem. And beauty consists in order (II 9, unica, 6). The beauty and perfection of the universe result from unity.

Platonic concepts: the one, the true and the good, and to each of them there is a differnt kind of causality can be attributed (cf. p. 36):

the one - efficient causality

the good - final causality

the true - formal causality

And the beautiful embraces all these causes.

2) the rational structure of beauty: it is quite striking for Bonaventure. Not only does the rationality of beautiful consists in the above mentioned order and proportion, but also in the rational reflection which follows the delight which one experiences at the presence of what is beautiful. Beauty leads to love. The delight is experienced in the presence of the beautiful in a spontanious way and without reflection. Afterwards there follows an act of the intellect which inquires why these objects produce their pleasant effects and what constitutes the pleasure that result from their perception. (Hoc est autem cum quaeritur ratio pulchri, suavis et salubris; et invenitur, quod haec est proportio aequalitatis. Ratio autem aequalitatis est eadem in magnis et parvis nec extenditur dimensionibus nec succedit seu transit cum transeuntibus nec motibus alteratur). In this point St. Bonaventure differs from St. Thomas, the latter proposes that an element of grandeur is needed for an object to be considered beautiful. What makes the things beautiful is the beauty itself. Beauty, while it delights, does not fully satisfy, but leads one to seek further on, as Bonaventure wrote: "Scientia reddit opus pulcrum, voluntas reddit utile, persevarantia reddit stabile. Primum est in rationali, secundum in concupiscibili, tertium in irascibili" (De Red. Art. ad Theol. 13).

3) The Christo-centric theology of Bonaventure leads him to take scars as beautifying the body, it is also a Franciscan tradition as the Franciscans confide themselves to the Amor Pauperis Crucifixi. This Christo-centric theology is supposed by some researchers to be manifested in the depiction of Christ as the Creator, for example at the portal of Cathedral Chartres. At the entrance of Chartres Cathedral one can see: the Creator is not shown as an image of God the Father, but is Christ. There is another picture showing Christ as Creator (from a manuscript of the 13th. century):

Father Boehner of the Franciscan Order pointed out, that the Frecos Stanza della Segnatura of Raphael was inspired by Franciscan thought, and that the textual source for it is the Prologue to Bonaventure's Breviloquium. In this series of frescos, we can see the Cardinal himself depicted, together with Pope Sixtus IV, who canonized him. (on the right side beneath, the one with the Cardinal's hat).

4) the natural and supernatural Beauty

Natural Beauty of the Soul: imago Dei - memoria, intellectus, voluntas - philosophical virtues; supernatural Beauty of the soul - theological virtues.

Labels:

Latin,

Philosophy,

Theology

Thursday, 15 July 2010

Pope Benedict on Bonaventure (His book: The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure)

A great book. Before I go into details, I want to enhance some important points and thoughts which occurred to me while reading:

1) The notion of history with an emphasis on the future in the theology of Bonaventure is quite interesting, Pope Benedict could be thinking of the Council Document "Gaudium et Spes" while writing;

2) the Notion of Tradition is interesting, against a static understanding of Tradition, this point, according to my understanding, is responsible for the "Hermeneutic of Continuity" of our Holy Father;

3) The development of the understanding of the Scripture;

On the 14th. of July, the Church celebrated the Feast Day of St. Bonaventure, the Doctor Seraphicus. Already at the age of 36 he was elected the seventh Superior General of the Franciscan Order. He doesn't belong to the most famous or the popular saints, though he was already raised to the altar on the on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the Church in the year 1588 by Pope Sixtus V. Nevertheless, Saint Bonaventure is not only a key figure in the history of philosophy and theology, his thought is even today of actuality, because his thinking is important for a better understanding of the theology of our Holy Father Benedict XVI.

Our Holy Father wrote as a young man his qualification's writing for a teaching position (Habilitationschrift) on the theology of St. Bonaventure (engl. translation by Zachary Hayes OFM, The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1971), in which the young theologian Joseph Ratzinger explored Bonaventure's attitude to Joachim of Fiores conception of history and prophecy. The abbot Joachim was a controversial figure in the Church history. He was considered by many as a Saint, though never officially approved, and his Feast Day was celebrated, unofficially, on the 29th. of May. And Dante made him immortal in the Divina Comedia, as standing at the side of St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure:

... e lucemini da lato

il Calavrese abate Gioachino

de spirito profetico dotato. (Parad., XII, 130-141)

But Joachim's teaching on the Trinity was criticised by the famous Peter Lombard, whose Sententiae was generally used as a textbook in the scholastics. Peter Lombard opined that Joachim presented a kind of Quartenitas, which took the Trinity as fourth unity besides the God Father, Son and the Holy Ghost. And some other points of Joachim's teaching were examined in year 1254, though he was never officially accused of heresy by the Church. Nevertheless, his followers, the Joachimites were condemned by Pope Alexander IV. in 1256.

In his thesis, Joseph Ratzinger takes a close look at Bonaventure's Collationes in Hexaemeron, which presents a fundamental treatment of the theology of history. Through careful textual analysis, Ratzinger shows that in difference to the traditional schema of seven ages, which goes back to Augustine (De civitate Dei ), or the schema of five ages based on the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Mt. 20, 1-16). Bonaventure offers a new schema of two ages which consists of the age of the Old Law and the New Law. Significant for Bonaventure's theology of history is also the inner-worldly, inner-historical messianic hope, while he rejects the view that with Christ the highest degree of inner-historical fulfilment is already realized so that only an eschatological hope for that which lies beyond all history is left (op. cit. 14). The future has its seeds in the past, and history is not a concatination of blind and chance happenings. With this, the rational structure of history is decisively affirmed. The real point, thus writes Ratzinger, is not the understanding of the past, but prophecy about that which is to come. But a knowledge of the past is necessary for the grasp of the future.

Though Bonaventure borrowed the two ages schema from Joachim, he did condemn the latter's idea of an eternal Gospel, which was supposed to take the place of the New Testament. And whilst Joachim expresses the idea of a new Order in which the ecclesia comtemplativa makes up the final age, while Bonaventures sees the new Order only as a fuller insight into the Scripture. In opposition to the Spirituals led by figures like Joachim and Johannes of Parma, Bonaventure stressed that Francis' own eschatological form of life could not exist as an institution in this world; "it could only be realized as a break-through of grace in the individual until such time as the God-given hour would arrive at which the world would be transformed into its final form of existence" (op. cit. 51).

"Francis is the apocalyptic angel of the seal from whom should come the final People of God, the 144,000 who are sealed. This final people of God is a community of contemplative men; in this community the form of life realized in Francis will become the general form of life. It will be the lot of this People to enjoy already in this world the peace of the seventh day which is to precede the Parousia of the Lord. [...] When this time arrives, it will be a time of contemplatio, a time of the full understanding of Scripture, and in this respect, a time of the Holy Spirit who leads us into the fullness of the truth of Jesus Christ" (op. cit. 54-55).

2. revelation: Bonaventure didn't talk of the "revelation" like we do today in the Fundamental Theology, but of "revelations". Three meanings in the works of Bonaventure: 1) In the Hexaemeron, revelatio means the unveiling of the future; 2) the hidden "mystical" meaning of Scripture; 3) that imageless unveiling of the divine reality which takes place in the mystical ascent (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite).

According to Bonaventure, the goal of Chrisitan learning is Wisdom, which can be divided into the following degrees:

sapientia multiformis - Epistle to the Ephesians

sapientia omniformis - Salomon

sapientia nulliformis - the mystic approaches in silents to the threshold of the mystery of the eternal God in the night of the intellect (Paul taught it to Timothy and Dionysius)

Bonaventure doesn't refer to the Scriptures themselves as "revelation". Instead, the revelation for him is the spiritual sense of Scripture.

Three visions (like Rupert of Deutz and St. Augustine): visio corporalis, visio spiritualis, viso intellectualis. Bonaventure holds that the content of faith is not found in the letter of Scripture but in the spiritual meaning lying behind the letter. But this view ought not to be understood as a kind of subjective actualism. because the deep meaning of Scripture is not left up to the whim of each individual. Instead, the content of the Faith "has already been objectified in part in the teachings of the Fathers and in theology so that the basic lines are accesible simple by the acceptance of the Catholic Faith. [...] Only Scripture as it is understood in faith is truly holy Scripture. Consequently, Scripture in the full sense is theology" (op. cit. 67).

Bonaventure believes that there is a gradual, historical, progressive development in the understanding of the Scripture which was in no way closed.

3) the Concept of Tradition and the Franciscan Order

According to Martin Grabmann, for Hugo of St. Victor, Scripture and the Fathers flow together into one great Scriptura Sacra. And at the time of Bonaventure, the Canon was set down for him as it stands today. But St. Francis challenged with his life according to the Sermon on the Mount this overtly statistic concept of Tradition.

4) Bonaventure in context of his time

under the influence of Rupert of Deutz (the emphasis on the future), Honorius of Autun and Anselm of Havelberg (the eschatological aspect of history).

"In contrast with Aquinas, Bonaventure expressly recognized Joachim's Old Testament exegesis and adopted it as his own. In this case, Thomas is more an Augustinian than is Bonaventure. [...] But the difference that separates Bonaventure from Joachim is greater than it may seem at first. Bascially he is in agreement with the Thomistic critique, for he also affirms a Christo-centrism. Bonaventure does not accept the notion of an age of the Holy Spirit which destroyed the central position of Christ in the Joachimite view" (op. cit. 117).

5) the Anti-Aristotelism of Bonaventure:

for a Christian understanding of time. For Aristotle, the world is eternal, which is contra the Christian teaching.

Philosophy as a "lignum scientiae boni et mali". but also as the Beast from the Abyss (Hexaemeron XVI), reason, the Harlot and the prophecy of the end of rational theology.

1) The notion of history with an emphasis on the future in the theology of Bonaventure is quite interesting, Pope Benedict could be thinking of the Council Document "Gaudium et Spes" while writing;

2) the Notion of Tradition is interesting, against a static understanding of Tradition, this point, according to my understanding, is responsible for the "Hermeneutic of Continuity" of our Holy Father;

3) The development of the understanding of the Scripture;

On the 14th. of July, the Church celebrated the Feast Day of St. Bonaventure, the Doctor Seraphicus. Already at the age of 36 he was elected the seventh Superior General of the Franciscan Order. He doesn't belong to the most famous or the popular saints, though he was already raised to the altar on the on 14 April 1482 by Pope Sixtus IV and declared a Doctor of the Church in the year 1588 by Pope Sixtus V. Nevertheless, Saint Bonaventure is not only a key figure in the history of philosophy and theology, his thought is even today of actuality, because his thinking is important for a better understanding of the theology of our Holy Father Benedict XVI.

Our Holy Father wrote as a young man his qualification's writing for a teaching position (Habilitationschrift) on the theology of St. Bonaventure (engl. translation by Zachary Hayes OFM, The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure, Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1971), in which the young theologian Joseph Ratzinger explored Bonaventure's attitude to Joachim of Fiores conception of history and prophecy. The abbot Joachim was a controversial figure in the Church history. He was considered by many as a Saint, though never officially approved, and his Feast Day was celebrated, unofficially, on the 29th. of May. And Dante made him immortal in the Divina Comedia, as standing at the side of St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure:

... e lucemini da lato

il Calavrese abate Gioachino

de spirito profetico dotato. (Parad., XII, 130-141)

But Joachim's teaching on the Trinity was criticised by the famous Peter Lombard, whose Sententiae was generally used as a textbook in the scholastics. Peter Lombard opined that Joachim presented a kind of Quartenitas, which took the Trinity as fourth unity besides the God Father, Son and the Holy Ghost. And some other points of Joachim's teaching were examined in year 1254, though he was never officially accused of heresy by the Church. Nevertheless, his followers, the Joachimites were condemned by Pope Alexander IV. in 1256.

In his thesis, Joseph Ratzinger takes a close look at Bonaventure's Collationes in Hexaemeron, which presents a fundamental treatment of the theology of history. Through careful textual analysis, Ratzinger shows that in difference to the traditional schema of seven ages, which goes back to Augustine (De civitate Dei ), or the schema of five ages based on the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Mt. 20, 1-16). Bonaventure offers a new schema of two ages which consists of the age of the Old Law and the New Law. Significant for Bonaventure's theology of history is also the inner-worldly, inner-historical messianic hope, while he rejects the view that with Christ the highest degree of inner-historical fulfilment is already realized so that only an eschatological hope for that which lies beyond all history is left (op. cit. 14). The future has its seeds in the past, and history is not a concatination of blind and chance happenings. With this, the rational structure of history is decisively affirmed. The real point, thus writes Ratzinger, is not the understanding of the past, but prophecy about that which is to come. But a knowledge of the past is necessary for the grasp of the future.

Though Bonaventure borrowed the two ages schema from Joachim, he did condemn the latter's idea of an eternal Gospel, which was supposed to take the place of the New Testament. And whilst Joachim expresses the idea of a new Order in which the ecclesia comtemplativa makes up the final age, while Bonaventures sees the new Order only as a fuller insight into the Scripture. In opposition to the Spirituals led by figures like Joachim and Johannes of Parma, Bonaventure stressed that Francis' own eschatological form of life could not exist as an institution in this world; "it could only be realized as a break-through of grace in the individual until such time as the God-given hour would arrive at which the world would be transformed into its final form of existence" (op. cit. 51).

"Francis is the apocalyptic angel of the seal from whom should come the final People of God, the 144,000 who are sealed. This final people of God is a community of contemplative men; in this community the form of life realized in Francis will become the general form of life. It will be the lot of this People to enjoy already in this world the peace of the seventh day which is to precede the Parousia of the Lord. [...] When this time arrives, it will be a time of contemplatio, a time of the full understanding of Scripture, and in this respect, a time of the Holy Spirit who leads us into the fullness of the truth of Jesus Christ" (op. cit. 54-55).

2. revelation: Bonaventure didn't talk of the "revelation" like we do today in the Fundamental Theology, but of "revelations". Three meanings in the works of Bonaventure: 1) In the Hexaemeron, revelatio means the unveiling of the future; 2) the hidden "mystical" meaning of Scripture; 3) that imageless unveiling of the divine reality which takes place in the mystical ascent (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite).

According to Bonaventure, the goal of Chrisitan learning is Wisdom, which can be divided into the following degrees:

sapientia multiformis - Epistle to the Ephesians

sapientia omniformis - Salomon

sapientia nulliformis - the mystic approaches in silents to the threshold of the mystery of the eternal God in the night of the intellect (Paul taught it to Timothy and Dionysius)

Bonaventure doesn't refer to the Scriptures themselves as "revelation". Instead, the revelation for him is the spiritual sense of Scripture.

Three visions (like Rupert of Deutz and St. Augustine): visio corporalis, visio spiritualis, viso intellectualis. Bonaventure holds that the content of faith is not found in the letter of Scripture but in the spiritual meaning lying behind the letter. But this view ought not to be understood as a kind of subjective actualism. because the deep meaning of Scripture is not left up to the whim of each individual. Instead, the content of the Faith "has already been objectified in part in the teachings of the Fathers and in theology so that the basic lines are accesible simple by the acceptance of the Catholic Faith. [...] Only Scripture as it is understood in faith is truly holy Scripture. Consequently, Scripture in the full sense is theology" (op. cit. 67).

Bonaventure believes that there is a gradual, historical, progressive development in the understanding of the Scripture which was in no way closed.

3) the Concept of Tradition and the Franciscan Order

According to Martin Grabmann, for Hugo of St. Victor, Scripture and the Fathers flow together into one great Scriptura Sacra. And at the time of Bonaventure, the Canon was set down for him as it stands today. But St. Francis challenged with his life according to the Sermon on the Mount this overtly statistic concept of Tradition.

4) Bonaventure in context of his time

under the influence of Rupert of Deutz (the emphasis on the future), Honorius of Autun and Anselm of Havelberg (the eschatological aspect of history).

"In contrast with Aquinas, Bonaventure expressly recognized Joachim's Old Testament exegesis and adopted it as his own. In this case, Thomas is more an Augustinian than is Bonaventure. [...] But the difference that separates Bonaventure from Joachim is greater than it may seem at first. Bascially he is in agreement with the Thomistic critique, for he also affirms a Christo-centrism. Bonaventure does not accept the notion of an age of the Holy Spirit which destroyed the central position of Christ in the Joachimite view" (op. cit. 117).

5) the Anti-Aristotelism of Bonaventure:

for a Christian understanding of time. For Aristotle, the world is eternal, which is contra the Christian teaching.

Philosophy as a "lignum scientiae boni et mali". but also as the Beast from the Abyss (Hexaemeron XVI), reason, the Harlot and the prophecy of the end of rational theology.

Labels:

Pope Benedict,

Theology

Monday, 12 July 2010

Carpe diem!

Today I picked up occasionally the edition of Horace's Odes and Epodes, edited by the Latinist Bernard Kytzler for students (Reclam 2000). Though I found initially Horace's world foreign to me, his carmen I, XI which I happened to read today struck me directly in the heart. It is written in Asclepiadeus maior (---uu- | -uu- | -uu-uu). The phrase "carpe diem" emerges in the last verse. An outworn phrase used to urge people to enjoy the life. But indeed I find it not so jolly as it seems. If you don't think of the nearing death, you won't be in need of urging yourself to grasp the fleeing day. How is it possible to get hold of the time, I ask you mate? Especially the word "pati" in the third verse betrayed the sadness hidden behind the seemingly careless tone of the poet. And the first lines of this poem begin directly with the thought on Death. It reminds me of the poems of the baroque era in which the poet urges his beloved woman not to hesitate to accept his love, because the snow of her shoulders will be ashes tomorrow.

Horatius carmen I, XI:

Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi

finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios

temptaris numeros. ut melius, quidquid erit, pati.

seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam,

quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare

Tyrrhenum: sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi

spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas: carpe diem quam minimum credula postero.

Horatius carmen I, XI:

Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi

finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios

temptaris numeros. ut melius, quidquid erit, pati.

seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam,

quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare

Tyrrhenum: sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi

spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas: carpe diem quam minimum credula postero.

Labels:

Latin

Sunday, 11 July 2010

Cor, quare me flere facis?

Cor stultum, putas quod iste vir me puellam miseram olim amavit? Ego nescio utrum hoc verum est. Nec audeo interrogare me ipsum utrum. Solum flere volo. Mens mea, mihi nullam responsionem da, cor meum franges.

Mens, cor, cur me affligitis? Amo, et amare desistere non possum. Umbram amo, animam pulchram amo. Mens, noli docere me quid prudens est, quia timeo me numquam somniaturam esse. Sed somniare volo. Cor, quare me flere facis? Somnium istud bellulum est. Cor, quare fleo quamvis somnio? Fleo veraciter in somnio.

Cor meum iam fractum est.

Mens, cor, cur me affligitis? Amo, et amare desistere non possum. Umbram amo, animam pulchram amo. Mens, noli docere me quid prudens est, quia timeo me numquam somniaturam esse. Sed somniare volo. Cor, quare me flere facis? Somnium istud bellulum est. Cor, quare fleo quamvis somnio? Fleo veraciter in somnio.

Cor meum iam fractum est.

Saturday, 10 July 2010

Eriugena's Immediate Influence (Note on the same book of O'Meara, Chapter 11)

In the Gesta episcoporum Autissiodorensium one reads that Wicbald (Guibaud), Bishop of Auxerre (879), was a disciple of Eriugena.

Eriugena was in the palace school of Charles the Bald. Indications show that he remained there from the early fifties until perhaps the late seventies of the ninth century. But it is unknown where this palace school was. It might have been in Laon, or in the neighbourhood, at Quierzy or Compiègne.

Two persons are especially important: Wulfad and Winibert. The Periphyseon was dedicated to Wulfad. Wulfad was a cleric of Reims, ordained by Ebbon but unrecognized by Hincmar, he became tutor of Charles the Bald's son Carloman (854-60), than abbot of Montierender (855-6), abbot of Saint-Médard at Soisson (858), abbot of Rebais (after 860), finally archbishop of Bourges. *(very important fact!):

"A list of some thirty-one books in his library show that it contained many of the same Greek authors as are found in Laon. It also contained Eriugena's translation of the Pseudo-Dionysius and the Quaestiones ad Thalassium of Maximus the Confessor as well as the Periphyseon. The list itself was written on the penultimate leaf of a volume containing Eriugena's translation of Maximus's Ambigua" (p. 199).

Manuscript Laon 24 contains a letter to a certain dominus Winibertus (according to J.J. Contreni the abbot of Schuttern in the diocese of Strasbourg) in which Eriugena expresses regret that he and Winibert had been separated so that their work on Martinaus Capella had become difficult.

Martin the Irishman, who taught at the cathedral school in Laon, belonged to the group of Irish in Laon whom Eriugena knew there. Martin used poems of Eriugena in his handbook MS Laon 444.

MS Paris BN lat. 10307 contains extracts from the Greek-Latin glossary of Martin and also a verse concerning Fergus and two distichs identified as Eriugena's by C. Leonardi.

Fergus was a close friend of Sedulius. Both Sedulius and Fergus are metioned in the marginalia of the ninth-century Codex Bernensis 363 along with Eriugena and some twelve other Irish contemparies. Also included in the marginalia are Gottschalk, Hincmar, and Ratramnus. Authors referred to in the MS are Donatus, Fulgentius, Hadrian, Honoratus, Isidore, Martinaus Capella, Priscian, Sergius, and Virgilius. The combination of all these naems of Eriugena's contemporaries suggest a common interest in the themes associated with the authors detailed. The name of Eriugena is entered over and over again aomong the marginalia of this manuscript, opposite passages relevant to Eriugena's teaching, and it is clear that the glossators knew the Periphyseon. Fergus, described as a grammaticus, is probably also to be associated with Eriugena and Bishop Pardulus of Laon in relation to a medicament recommended for the removal of unwanted hair (curious thing).

Two pupils of Eriugena: Elias, an Irishman, later bishop of Angoulême (861-75) and Wicbald, later bishop of Auxerre (879-87). In biblical glosses attributed to Eriugena some fifty words in Old Irish are used as glosses on the Old Testament.

Others who were influenced by him: Almannus of Hautvillers and Hucbald of St. Amand, the latter made a florilegium of Eriugenan thoughts.

Heiric of Auxerre, author of Life of St Germanus, Collectanea, Homiliary. He borrowed from Eriugena in his Life of St. Germanus and Homiliary. In the Life of St. Germanus: the same language, the same themes, the same insertion of occasional Greek words or verses. Also his Homiliaryis heavily indebted to Eriugena's Homily on the Prolouge to St. John's Gospel. Heiric was in his Life of St. Germanus indebted to Periphyseon I-III. The Homily reveals that he knew Periphyseon IV and V as well.

Three ancient texts were glossed by those engaged in teaching and learning: Martianus Capella's De nuptiis (glossed by Eriugena and Marin); Boethius's Opuscula sacra and the Categoriae decem (a worled attributed to Augustine and used extensively by Eriugena in the first book of Periphyseon).

Heiric might have become a follower of Eriugena through his teacher Remigius of Auxerre Remigius might have been born in Ireland in the early forties. He is first identified as a monk at the abbey of St-Germain at Auxerre, wrote a commentary on the Consolatio of Boethius and a commentary on Martianus Capella.

Eriugena was in the palace school of Charles the Bald. Indications show that he remained there from the early fifties until perhaps the late seventies of the ninth century. But it is unknown where this palace school was. It might have been in Laon, or in the neighbourhood, at Quierzy or Compiègne.

Two persons are especially important: Wulfad and Winibert. The Periphyseon was dedicated to Wulfad. Wulfad was a cleric of Reims, ordained by Ebbon but unrecognized by Hincmar, he became tutor of Charles the Bald's son Carloman (854-60), than abbot of Montierender (855-6), abbot of Saint-Médard at Soisson (858), abbot of Rebais (after 860), finally archbishop of Bourges. *(very important fact!):

"A list of some thirty-one books in his library show that it contained many of the same Greek authors as are found in Laon. It also contained Eriugena's translation of the Pseudo-Dionysius and the Quaestiones ad Thalassium of Maximus the Confessor as well as the Periphyseon. The list itself was written on the penultimate leaf of a volume containing Eriugena's translation of Maximus's Ambigua" (p. 199).

Manuscript Laon 24 contains a letter to a certain dominus Winibertus (according to J.J. Contreni the abbot of Schuttern in the diocese of Strasbourg) in which Eriugena expresses regret that he and Winibert had been separated so that their work on Martinaus Capella had become difficult.

Martin the Irishman, who taught at the cathedral school in Laon, belonged to the group of Irish in Laon whom Eriugena knew there. Martin used poems of Eriugena in his handbook MS Laon 444.

MS Paris BN lat. 10307 contains extracts from the Greek-Latin glossary of Martin and also a verse concerning Fergus and two distichs identified as Eriugena's by C. Leonardi.

Fergus was a close friend of Sedulius. Both Sedulius and Fergus are metioned in the marginalia of the ninth-century Codex Bernensis 363 along with Eriugena and some twelve other Irish contemparies. Also included in the marginalia are Gottschalk, Hincmar, and Ratramnus. Authors referred to in the MS are Donatus, Fulgentius, Hadrian, Honoratus, Isidore, Martinaus Capella, Priscian, Sergius, and Virgilius. The combination of all these naems of Eriugena's contemporaries suggest a common interest in the themes associated with the authors detailed. The name of Eriugena is entered over and over again aomong the marginalia of this manuscript, opposite passages relevant to Eriugena's teaching, and it is clear that the glossators knew the Periphyseon. Fergus, described as a grammaticus, is probably also to be associated with Eriugena and Bishop Pardulus of Laon in relation to a medicament recommended for the removal of unwanted hair (curious thing).

Two pupils of Eriugena: Elias, an Irishman, later bishop of Angoulême (861-75) and Wicbald, later bishop of Auxerre (879-87). In biblical glosses attributed to Eriugena some fifty words in Old Irish are used as glosses on the Old Testament.

Others who were influenced by him: Almannus of Hautvillers and Hucbald of St. Amand, the latter made a florilegium of Eriugenan thoughts.

Heiric of Auxerre, author of Life of St Germanus, Collectanea, Homiliary. He borrowed from Eriugena in his Life of St. Germanus and Homiliary. In the Life of St. Germanus: the same language, the same themes, the same insertion of occasional Greek words or verses. Also his Homiliaryis heavily indebted to Eriugena's Homily on the Prolouge to St. John's Gospel. Heiric was in his Life of St. Germanus indebted to Periphyseon I-III. The Homily reveals that he knew Periphyseon IV and V as well.

Three ancient texts were glossed by those engaged in teaching and learning: Martianus Capella's De nuptiis (glossed by Eriugena and Marin); Boethius's Opuscula sacra and the Categoriae decem (a worled attributed to Augustine and used extensively by Eriugena in the first book of Periphyseon).

Heiric might have become a follower of Eriugena through his teacher Remigius of Auxerre Remigius might have been born in Ireland in the early forties. He is first identified as a monk at the abbey of St-Germain at Auxerre, wrote a commentary on the Consolatio of Boethius and a commentary on Martianus Capella.

Labels:

Latin

Friday, 9 July 2010

Animals in Paradise (a Poem by William Blake)

Talking about animals in Paradise, I remember a poem written by William Blake:

(Though the interpreters are not in full agreement whether this poem can be taken as a picture of terrestrial paradise, E.D. Hirsch is the one who suggested this reading, cf. Hirsch, E.D.: Innocence and Experience: An Introduction to Blake. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1964).

The Little Girl Lost

In futurity

I prophesy

That the earth from sleep

(Grave the sentence deep)

Shall arise, and seek

For her Maker meek;

And the desert wild

Become a garden mild.

In the southern clime,

Where the summer's prime

Never fades away,

Lovely Lyca lay.

Seven summers old

Lovely Lyca told.

She had wandered long,

Hearing wild birds' song.

'Sweet sleep, come to me,

Underneath this tree;

Do father, mother, weep?

Where can Lyca sleep?

'Lost in desert wild

Is your little child.

How can Lyca sleep

If her mother weep?

'If her heart does ache,

Then let Lyca wake;

If my mother sleep,

Lyca shall not weep.

'Frowning, frowning night,

O'er this desert bright

Let thy moon arise,

While I close my eyes.'

Sleeping Lyca lay,

While the beasts of prey,

Come from caverns deep,

Viewed the maid asleep.

The kingly lion stood,

And the virgin viewed:

Then he gambolled round

O'er the hallowed ground.

Leopards, tigers, play

Round her as she lay;

While the lion old

Bowed his mane of gold,

And her breast did lick

And upon her neck,

From his eyes of flame,

Ruby tears there came;

While the lioness

Loosed her slender dress,

And naked they conveyed

To caves the sleeping maid.

(Though the interpreters are not in full agreement whether this poem can be taken as a picture of terrestrial paradise, E.D. Hirsch is the one who suggested this reading, cf. Hirsch, E.D.: Innocence and Experience: An Introduction to Blake. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1964).

The Little Girl Lost

In futurity

I prophesy

That the earth from sleep

(Grave the sentence deep)

Shall arise, and seek

For her Maker meek;

And the desert wild

Become a garden mild.

In the southern clime,

Where the summer's prime

Never fades away,

Lovely Lyca lay.

Seven summers old

Lovely Lyca told.

She had wandered long,

Hearing wild birds' song.

'Sweet sleep, come to me,

Underneath this tree;

Do father, mother, weep?

Where can Lyca sleep?

'Lost in desert wild

Is your little child.

How can Lyca sleep

If her mother weep?

'If her heart does ache,

Then let Lyca wake;

If my mother sleep,

Lyca shall not weep.

'Frowning, frowning night,

O'er this desert bright

Let thy moon arise,

While I close my eyes.'

Sleeping Lyca lay,

While the beasts of prey,

Come from caverns deep,

Viewed the maid asleep.

The kingly lion stood,

And the virgin viewed:

Then he gambolled round

O'er the hallowed ground.

Leopards, tigers, play

Round her as she lay;

While the lion old

Bowed his mane of gold,

And her breast did lick

And upon her neck,

From his eyes of flame,

Ruby tears there came;

While the lioness

Loosed her slender dress,

And naked they conveyed

To caves the sleeping maid.

Labels:

Literatur

Thursday, 8 July 2010

Festina lente - What Erasmus can make out of an adage

The Adagia of Erasmus of Rotterdam provides an example of the encyclopaedic and polihistorical character of the Humanist scholarship.

Just reading the Adagium Festina lente, it begins with etymological observations and citations from ancient authors like Aristophanes, Homer and Hesiod, and moves on to rhetoric and emblematic observations. He mentions a coin of Vespasian, whose backside shows a dolphin who embraces an anchor. However, what most amusing is how Erasmus makes out of this proverb a philosophy of time: dolphin is the symbol for quickness, whilst the anchor is the symbol for slowness. Together they display exactly this adagium. Erasmus goes on to a philosophical excursion and refers to Aristotle. What strikes me is how unaristotelian his account of the view of Aristotle on time is: he mentions the impetus theory, according to which the impetus is the smallest and indivisible unit of time. It might be basing on the influence of late medieval natural philosophy, but it is not at all Aristotelian as Aristotle opposes to the atom theory of Democrit. According to Aristotle there is no smallest unit of time.

Just a note.

P.S. a quick search brings on to very interesting facts: the dolphin in the heraldry: John Vinycomb: Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, 1909.

And Alciato expanded on this emblema (from http://www.mun.ca/alciato/, a wonderful discovery! the whole Liber Emlematum of Alciato as online edition!). Though in a different meaning than Erasmus:

Princeps subditorum incolumitatem procurans

Titanii quoties conturbant aequora fratres,

Tum miseros nautas anchora iacta iuvat:

Hanc pius erga homines Delphin complectitur, imis

Tutius ut possit figier illa vadis.

Quam decet haec memores gestare insignia Reges,

Anchora quod nautis, se populo esse suo.

Commentary to this Emblema (from the same project: http://www.mun.ca/alciato/index.html):

The "Titan brothers" are the winds. The kindness of dolphins towards men was written about very early (eg, Aristotle History of Animals book 5). The anchor as a sign of political stability appears in a number of classical authors.

Erasmus in his Adages has a full discussion of the anchor and dolphin, but interprets it quite differently from Alciato, under the heading of "Festina lente" or "Hasten slowly" where the swift movement of the dolphin is tempered by the stability of the anchor (2.1.1; trans Collected Works of Erasmus 33:3-17). The symbol appeared on an ancient coin of the emperor Titus Vespasian in AD 80. Apparently (note in CWE 33:340) the juxtaposition of anchor and dolphin had been associated with the god Neptune and the coin was issued in propitiation for the eruption of Vesuvius the year before. Erasmus sees the symbol as a hieroglyphic, which he explains in a long passage. Aldus Manutius (Aldo Manuzio, the Venetian printer, d 1515), published the 1508 edition of Erasmus' Adages, and in his adage 2.1.1 Erasmus tells how Aldus showed him the ancient coin of Vespasian. Aldus had been familiar with this symbol for some time. It appeared in Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published by Aldus in 1499, as a "hieroglyphic" symbol. Soon after Aldus began to use the anchor and dolphin as his mark, and it was retained by his family after his death (you can see it on the title page of the 1546 edition). It is perhaps the most famous trademark in the history of Western printing.

Just reading the Adagium Festina lente, it begins with etymological observations and citations from ancient authors like Aristophanes, Homer and Hesiod, and moves on to rhetoric and emblematic observations. He mentions a coin of Vespasian, whose backside shows a dolphin who embraces an anchor. However, what most amusing is how Erasmus makes out of this proverb a philosophy of time: dolphin is the symbol for quickness, whilst the anchor is the symbol for slowness. Together they display exactly this adagium. Erasmus goes on to a philosophical excursion and refers to Aristotle. What strikes me is how unaristotelian his account of the view of Aristotle on time is: he mentions the impetus theory, according to which the impetus is the smallest and indivisible unit of time. It might be basing on the influence of late medieval natural philosophy, but it is not at all Aristotelian as Aristotle opposes to the atom theory of Democrit. According to Aristotle there is no smallest unit of time.

Just a note.

P.S. a quick search brings on to very interesting facts: the dolphin in the heraldry: John Vinycomb: Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, 1909.

And Alciato expanded on this emblema (from http://www.mun.ca/alciato/, a wonderful discovery! the whole Liber Emlematum of Alciato as online edition!). Though in a different meaning than Erasmus:

Alciati Emblematum liber

Emblema CXLIVPrinceps subditorum incolumitatem procurans

Titanii quoties conturbant aequora fratres,

Tum miseros nautas anchora iacta iuvat:

Hanc pius erga homines Delphin complectitur, imis

Tutius ut possit figier illa vadis.

Quam decet haec memores gestare insignia Reges,

Anchora quod nautis, se populo esse suo.

Commentary to this Emblema (from the same project: http://www.mun.ca/alciato/index.html):

The "Titan brothers" are the winds. The kindness of dolphins towards men was written about very early (eg, Aristotle History of Animals book 5). The anchor as a sign of political stability appears in a number of classical authors.

Erasmus in his Adages has a full discussion of the anchor and dolphin, but interprets it quite differently from Alciato, under the heading of "Festina lente" or "Hasten slowly" where the swift movement of the dolphin is tempered by the stability of the anchor (2.1.1; trans Collected Works of Erasmus 33:3-17). The symbol appeared on an ancient coin of the emperor Titus Vespasian in AD 80. Apparently (note in CWE 33:340) the juxtaposition of anchor and dolphin had been associated with the god Neptune and the coin was issued in propitiation for the eruption of Vesuvius the year before. Erasmus sees the symbol as a hieroglyphic, which he explains in a long passage. Aldus Manutius (Aldo Manuzio, the Venetian printer, d 1515), published the 1508 edition of Erasmus' Adages, and in his adage 2.1.1 Erasmus tells how Aldus showed him the ancient coin of Vespasian. Aldus had been familiar with this symbol for some time. It appeared in Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published by Aldus in 1499, as a "hieroglyphic" symbol. Soon after Aldus began to use the anchor and dolphin as his mark, and it was retained by his family after his death (you can see it on the title page of the 1546 edition). It is perhaps the most famous trademark in the history of Western printing.

Labels:

Literatur

Wednesday, 7 July 2010

Sadness

Not in a creative state. Feelings and Thoughts all messed up. Sadness deep in heart. An inconsolable longing. Must get my acts together, desperately the mind tries to command. Where is my will? Suffer under the ἀκρασία, drifting with the stream, carried downstream like petals on the water surface. It carries me to nowhere. Only to the sea of indefinite width. No one is waiting at the end of the journey.

Lord have mercy on me!

Lord have mercy on me!

Tuesday, 6 July 2010

Christianization and Europe

In the Geschichte der Religiosität im Mittelalter Arnold Angenendt wrote:

By the way, I found a very lovely video about the brothers Ratzinger:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iArg7ZSjbc

Zunächst war Europa ein ethnischer, kultureller und religiöser Flickenteppich, der sich additiv aneinanderreihte, aber keinen den Gesamtraum übergreifenden Zusammenhalt besaß und somit auch keine gemeinsame Geschichte hatte. Erst die Missionierung, die von der Taufe Chlodwigs bis zur Christianisierung der baltischen Völker im 14. Jahrhundert tausend Jahre in Anspruch nahm, hat jenen inneren Verbund herbeigeführt, der Europa ausmacht. Dabei sind in großem Ausmaß Verluste und Zerstörungen, doch auch bedeutsame Gewinne zu verzeichnen, eben das neu geschaffene Europa.Without Christianity and Mission there would have been no Unity of Europe. Thus the process of secularisation is alarming as there would be no common ground for communication any more if the governments should get rid entirely of the Christian roots of their own culture. I think it must be one of the reasons why Pope Benedict established the Pontifical Council for the New Evangelisation of Europe.

By the way, I found a very lovely video about the brothers Ratzinger:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iArg7ZSjbc

Labels:

Pope Benedict

Sunday, 4 July 2010

Psalm 114 on Exodus

That is one of my favourite Church songs by Mozart (and easy to sing):

But I am still full of melancholy. The little cat is whining again, and inside me my heart too. I feed her again, and she is happy now, but I remain in the same state.

Psalm 114: Als aus Ägypten Israel (only the first and sixth verse available on Youtube)

The anonymous German (quite free) translation of Psalm 114 set by Mozart reads:

But I am still full of melancholy. The little cat is whining again, and inside me my heart too. I feed her again, and she is happy now, but I remain in the same state.

Psalm 114: Als aus Ägypten Israel (only the first and sixth verse available on Youtube)

The anonymous German (quite free) translation of Psalm 114 set by Mozart reads:

Als aus Ägypten Israel, vom Volke der Barbaren, gezogen aus dem Heidentum die Kinder Jakobs waren, da ward Judäa Gott geweiht und Israel gebenedeit zu seinem Reich und Erbe. Das Weltmeer sah's, erstaunt' und floh; der Jordan wich, floss klemmer, wie widder hüpften Berg' empor und Hügel wie die Lämmer, was war dir, Weltmeer, dass du flohst? Dir, Jordan, dass zurück du zohst? Was hüpften Berg' und Hügel? Vor ihres Gottes Gegenwart, durch den die Schöpfung lebet, vor Gottes Jakobs Angesicht hat Erd' und Meer gebebet, vor ihm, dess' mächt'ge Wunderkraft aus Stein und Felsen Seen schafft, aus Kiesel Wasserquellen. Nicht uns gib Ehre, Herr, nicht uns, dein Ruhm soll alles füllen; allein um der Erbarmungen, um deiner Wahrheit willen. In Dir nur ist Vollkommenheit, und all dein Tun Barmherzigkeit; preis sei nur deinem Namen! Daß nun nicht mehr mit Frevlerspott das Volk der Heiden fraget: Wo ist ihr allgewalt'ger Gott, der ihrer Sorge traget? Im Himmel thront Gott, unser Herr, und was er will, das schaffet er allmächtig, gütig, weise. Der Heiden Götzen, Silber, Gold, die nur durch sie entstehen, die haben Ohren, hören nicht, und Augen die nicht sehen, und Mund und Kehle, die nicht spricht. Sie riechen, tasten, gehen nicht mit Nase, Händen, Füssen. Gleich ihnen werde, der sie macht und der auf sie vertrauet; doch Israels und Aarons Haus hat auf den Herrn gebauet, und jeder Fromme hofft auf ihn. Darum wird Rettung ihm verlieh'n. Gott ist sein Schirm, sein Helfer! Stets war Gott unser eingedenk wenn Übels uns begegnet; er hat gesegnet Israel, hat Aarons Haus gesegnet. Der Herr liess allen, die ihn scheu'n, Erbarmung, Segen angedeih'n, vom Mind'sten bis zum Grössten. Noch ferner komm auch Gottes Heil auf euch und eure Kinder, stets werde seines Segens mehr und stets des Argen minder. Der Erd' und Himmel hat gemacht, der Herr sei seines Volks bedacht, schütz' uns, sein salig Erbe. Du gabst, Herr, dess' die Himmel sind, das Erdreich Menschensöhnen; von Toten, die der Abgrund schlingt, wird nicht dein Lob ertönen; doch wir, in denen Leben ist, wir preisen Dich von dieser Frist in ewig ew'ge Zeiten!

Labels:

Music

Friday, 2 July 2010

Petrarca: Canzoniere

Poor maiden! You are not born with honeyed mouth, never drank the nectar, never learned to sing in verses, never played a lyre. But how come that you, without the genius of a poet, should suffer his pain and languish? Let the poet sing for you, he, a luckier soul, could transfer his anguish into immortal melody (and I, though never learned Italian, type it in original as it is more beautiful than in translation), and teresa be an echo of his song:

132

S'amor non è, che dunque è quel ch'io sento?

Ma s'egli è amor, perdio, che cosa et quale?

Se bona, onde l'effecto aspro mortale?

Se ria, onde sì dolce ogni tormento?

S'a mia voglia ardo, onde 'l pianto e lamento?

S'a mal mio grado, il lamentar che vale?

O viva morte, o dilectoso male,

come puoi tanto in me, s'io nol consento?

Et s'io 'l consento, a gran torto mi doglio.

Fra sì contrari vènti in frale barca

mi trovo in alto mar senza governo,

sì lieve di saver, d'error sì carca

ch'i' medesmo non so quel ch'io mi voglio,

e tremo a mezza state, ardendo il verno.

There is a baroque German translation to it by Martin Opitz (Sonnet with Alexandrian verses)

Francisci Petrarchae (Sonnet XXI)

ISt Liebe lauter nichts / wie daß sie mich entzündet?

Ist sie dann gleichwol was / wem ist ihr Thun bewust?

Ist sie auch gut vnd recht / wie bringt sie böse Lust?

Ist sie nicht gut / wie daß man Frewd' auß jhr empfindet?

Lieb' ich ohn allen Zwang / wie kan ich schmertzen tragen?

Muß ich es thun / was hilfft's daß ich solch Trawren führ'?

Heb' ich es vngern an / wer dann befihlt es mir?

Thue ich es aber gern'/ vmb was hab' ich zu klagen?

Ich wancke wie das Graß so von den kühlen Winden

Vmb Vesperzeit bald hin geneiget wird / bald her:

Ich walle wie ein Schiff das durch das wilde Meer

Von Wellen vmbgejagt nicht kan zu Rande finden.

Ich weiß nicht was ich wil / ich wil nicht was ich weiß:

Im Sommer ist mir kalt / im Winter ist mir heiß.

132

S'amor non è, che dunque è quel ch'io sento?

Ma s'egli è amor, perdio, che cosa et quale?

Se bona, onde l'effecto aspro mortale?

Se ria, onde sì dolce ogni tormento?

S'a mia voglia ardo, onde 'l pianto e lamento?

S'a mal mio grado, il lamentar che vale?

O viva morte, o dilectoso male,

come puoi tanto in me, s'io nol consento?

Et s'io 'l consento, a gran torto mi doglio.

Fra sì contrari vènti in frale barca

mi trovo in alto mar senza governo,

sì lieve di saver, d'error sì carca

ch'i' medesmo non so quel ch'io mi voglio,

e tremo a mezza state, ardendo il verno.

There is a baroque German translation to it by Martin Opitz (Sonnet with Alexandrian verses)

Francisci Petrarchae (Sonnet XXI)

ISt Liebe lauter nichts / wie daß sie mich entzündet?

Ist sie dann gleichwol was / wem ist ihr Thun bewust?

Ist sie auch gut vnd recht / wie bringt sie böse Lust?

Ist sie nicht gut / wie daß man Frewd' auß jhr empfindet?

Lieb' ich ohn allen Zwang / wie kan ich schmertzen tragen?

Muß ich es thun / was hilfft's daß ich solch Trawren führ'?

Heb' ich es vngern an / wer dann befihlt es mir?

Thue ich es aber gern'/ vmb was hab' ich zu klagen?

Ich wancke wie das Graß so von den kühlen Winden

Vmb Vesperzeit bald hin geneiget wird / bald her:

Ich walle wie ein Schiff das durch das wilde Meer

Von Wellen vmbgejagt nicht kan zu Rande finden.

Ich weiß nicht was ich wil / ich wil nicht was ich weiß:

Im Sommer ist mir kalt / im Winter ist mir heiß.

Labels:

Literature

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)